Bias and Perception: How Dueling Truths Complicate Discipline

Bias and Perception: How Dueling Truths Complicate Discipline

A patient accuses her physician of abuse. He categorically denies it.

Both are telling the truth. Welcome to “parallax.”

Ms. Barnes waited anxiously as the radiologist studied the images from her mammogram. After a few minutes, Dr. Richards found her in the waiting room and waved her over, saying he wanted to show her what he had found. The viewing room was dimly lit and Ms. Barnes entered warily. The physician’s attempt at lighthearted banter only made her more nervous. Then as she inched closer to get a better look, Dr. Richards suggested she join him in front of his computer monitor.

What happened next is unclear. Ms. Barnes said the radiologist patted his leg and urged her to come sit on his knee. Dr. Richards said he simply tapped a nearby chair and invited his patient to “sit next to me.” At the regulatory board hearing, each accused the other of lying. Without any real evidence, the board sided with the vulnerable patient. Dr. Richards was suspended for six months and ordered to attend a remedial course on professional boundaries.

The suspended physician was still fuming when he enrolled in the remedial course a few weeks later. As he told his story to the other participants, many shared his outrage. Then the instructor asked a question that caught everyone by surprise. “What makes you think she was lying?”

Understanding the power of parallax

It can be difficult to accept, but the fact is people often perceive things so differently that each believes the other is mistaken, if not actually lying. A 2019 study from Stanford University found that personal bias not only influenced what subjects said they saw, it also influenced what they actually saw.

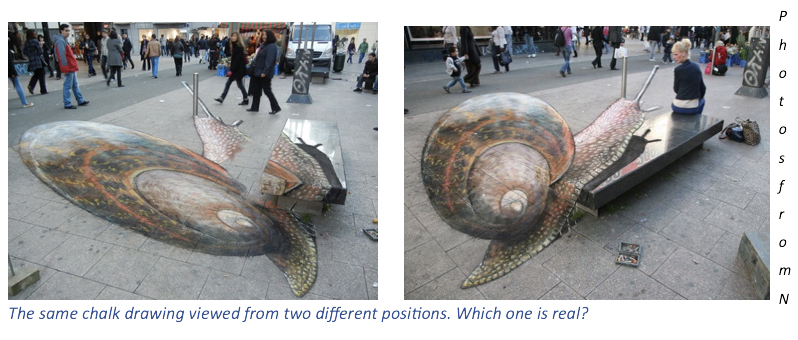

PBI founder, Stephen Schenthal, MD, refers to this phenomenon as “parallax,” the term scientists use to describe the way an object seems to shift position when the observer moves. Astronomers use parallax and trigonometry to calculate the distance of a star by measuring its apparent shift in position as the earth orbits the sun. Artists use the same principle to create incredible three-dimensional effects.

The important point about parallax is that two very different views of the same thing can be equally accurate. Both Dr. Richards’ and Ms. Barnes’ accounts of their encounter are faithful descriptions of what each experienced. His is colored by what he meant to say, hers by what she feared he meant.

Even our sense of touch is subject to parallax. When a male physician shifts a patient’s breast during a cardiac exam, her experience can be totally unlike his. She feels the unexpected touch as a sexual assault. He regards it as part of a routine procedure. Neither one is lying when they testify before the medical board.

Once you understand parallax, you can benefit from it in at least two ways. As lead author of the Stanford study, Yuan Chang Leong, told Psychology Today, “Knowing that others could truly be seeing things differently from us, and neither of us is necessarily closer to objective reality, we [are] better able to empathize with how they act and feel.”

This heightened empathy can help professionals who’ve been disciplined find their way back. According to Schenthal, practitioners who hope to recover need to move past their negative feeling towards their accusers. Before they can accept responsibility for their own actions, they need to stop feeling victimized and betrayed. “That’s a lot easier to do if you understand that your accusers are not out to get you,” he explained. “The patient believes the accusation they made is true. Even if you disagree with that belief, regulators have good reasons for accepting the patient’s account.”

Putting parallax to work

Parallax can also help practitioners protect themselves from the kind of situation Dr. Richards experienced. Once you understand that a patient is apt to perceive things differently from you, it’s your responsibility to do a better job of checking in with them to make sure you and they are on the same page.

It’s all about communication, says Jon Porter, healthcare attorney and PBI faculty member. He gives all his students the same advice: tell the patient what you are about to do; explain what you are doing; and review what you just did. Then stop and ask if they have any questions or concerns. “And don’t just listen to what they say. Pay attention to non-verbal signals, too,” he urges. A patient may be too intimidated or worried about offending you to say what’s on their mind. If you’re sensitive to their body language and tone of voice, you can help them say what’s troubling them. “Nine times out of ten,” said Porter, “you discover a misunderstanding that can be cleared up before it festers into something serious.”

Well-trained medical chaperones, also known as practice monitors, can play an important role as well. In the event of a dispute, they offer a neutral, third perspective, free of either the patient’s or the practitioner’s bias. More importantly, chaperones can pay close attention to those non-verbal signals Porter mentioned. If they notice signs of discomfort or concern, they can call attention to them and help facilitate the kind of frank exchange that is in everyone’s best interest.

No one is immune to parallax

Regulatory agencies, too, can benefit by considering the effects of parallax. One can assume that staff investigators who spend years exploring the seamier side of practitioners’ conduct, may be prone to developing a jaundiced view of the medical profession. When physicians like Dr. Richards profess their innocence, this unconscious bias may come into play.

Clinical board members new to a regulatory agency can also see things very differently. Just as investigators’ experience influences what they see, so regulatory members’ often more positive experiences affect their perception. Dr. Stephen Loyd was a nationally renowned expert on addiction medicine when he joined the Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners. He had a real passion for his work, based in part on his own experience as a recovering addict. The first case he heard concerned Dr. Stephen Lapaglia, a physician accused of over prescribing opioids.

Loyd told Rebecca Haw Allensworth, a law professor writing a book on regulatory boards, that “he had failed to see Dr. Lapaglia from a regulator’s perspective: as a threat to public safety. Rather, he saw him, at some level, as a fellow troubled physician” (see “Licensed to Pill”). Influenced by his unconscious bias, Loyd perceived only those parts of Lapaglia’s testimony that confirmed his view and reinstated the physician’s license. A month later, Loyd told Allensworth, “I was appointed by the Governor to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the people of Tennessee. I didn’t do that.”

Like everyone else, regulatory members and their staffs see the world from their own unique perspectives. That’s not a bad thing, as long as they realize that their perception is not the only one that counts. Had Loyd considered how his previous experience might be affecting his view of Lapaglia, he might have reached a very different conclusion.

Protect yourself at all times

Schenthal sees one additional benefit to understanding parallax. “No one ever thinks they are going to get in trouble — until they do,” he said. That’s why PBI’s first law of professional boundaries is, “Everyone has a violation potential.” Still, he explained, it is almost impossible to convince someone who has never had any problems that they too are vulnerable to committing a potentially career-ending violation. “People have trouble accepting that others don’t always see them the way they see themselves. I hear it all the time: ‘I’m a good person. How can they think that about me?’”

Understanding parallax helps people break through this barrier. Once a practitioner understands that everyone sees things from their own perspective, based on their own experiences and expectations, they begin to realize how easy it is for a patient to view something as hostile or threatening even when that’s not at all what was intended. It helps the practitioner grasp the first law and accept the need to protect themselves at all times (PBI’s third law of professional boundaries).

Had Dr. Richards understood the concept of parallax before he invited Ms. Barnes into the viewing room, he might have done a better job of communicating with her, making sure she understood why the room had to be dimly lit and why he was asking her to sit closer to the images he wanted to show her. He might have been more sensitive to Ms. Barnes’ reaction to his banter and taken steps to restore a more professional tone to the encounter. Most importantly, despite his long, unblemished record and proud commitment to the highest ethical standards, Dr. Richards would have started the day fully aware of his own vulnerability.

Related Resources:

Book:

Courses:

- PBI Navigating Professional Boundaries in Health Care (DR-2): This preventative risk management course discusses developing and implementing professional boundaries as a clinician.

- Managing Clinician-Patient Conflicts (CPC-2): Covers strategies for conflict management, deescalating tension, and understanding patients with personality disorders

- Medical Ethics and Professionalism (ME-15): One-day course addressing ethical crossings, enhancing professionalism, and mitigating risks.

- Professional Boundaries (PB-24): Three-day course focuses on establishing and maintaining boundaries, enhancing ethical decision making, and mitigating risks.