The TIMERS Analysis: A New Way of Understanding Civility

The TIMERS Analysis: A New Way of Understanding Civility

The following case is based on actual accounts by PBI Education course graduates. Names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy and identity of individuals.

On June 6, 2014, Dr. Jeffery Connors received two official communications from the hospital where he worked. There was a commendation in the morning for “exemplary patient care during the past six months,” followed by a stern warning in the afternoon about his “incivility” in a particular case. When he sat down with his supervisor to discuss the complaint, he joked that he was suffering from a severe case of whiplash.

Dr. Connors was surprised to learn that the complaint had come from Andrew, a nurse he worked with frequently and thought highly of. Andrew said that the physician had not only offended him personally but had so demeaned him in the eyes of a patient, Ms. Forbes, that it interfered with his ability to care for her. Even more shocking to Dr. Connors, Ms. Forbes confirmed the allegations.

The hospital initiated a remedial plan for Dr. Connors that mandated attendance at PBI Education’s course, Elevating Civility and Communication in Health Care. It wasn’t until the second day of the course that Dr. Connors began to understand what had gone wrong and how the two seemingly contradictory notes from the hospital were, in fact, closely related.

A new kind of checklist

Dr. Connors was not looking forward to taking the class. After mulling over what had happened that day in Ms. Forbes’ hospital room, he was tempted to shrug off Andrew’s complaint. The way Dr. Connors saw it, he had been patient, caring, and thorough throughout. He recalled only one significant interaction with the nurse. Andrew had intruded at one point to suggest that Ms. Forbes seemed worried by a comment Dr. Connors had meant to be reassuring. Dr. Connors checked with his patient to make sure she had understood him correctly, then continued the visit without further interruption.

On the second day of the course, the instructor, Catherine Caldicott, MD, introduced TIMERS©, a tool to aid in self-reflection developed by PBI Education. It was similar to a checklist in some ways. Like the checklists Dr. Connors used at the hospital, TIMERS was designed to encourage a methodical, step-by-step process. But in this case, the goal was not to remind clinicians of steps they already knew. Instead, TIMERS prompted them to consider potentially troubling aspects of their communication style they had not previously been aware of.

Each letter in the acronym suggested a key aspect of communication that might lead to perceptions of incivility:

T for Timing: Did you hurry the person you were talking to? Interrupt them? Rush ahead without allowing time for mental processing or questions?

I for Impressions: How did you come across? Did your non-verbal signals match what you were saying? Were you aware of the impact you were making?

M for Memory: What memories bubbled up during the conversation? Did past experiences color your interaction in any way?

E for Emotions: What were you feeling during the encounter? Were you able to keep your own emotions from spilling over into the professional situation?

R for Relativity: Each person in an encounter views it from a different angle. Did you consider how your words and behavior might appear to someone else?

S for Social Pressures: Did you feel obligated to be “a nice guy” or to have all the answers? How did these pressures influence your behavior?

Putting TIMERS to work

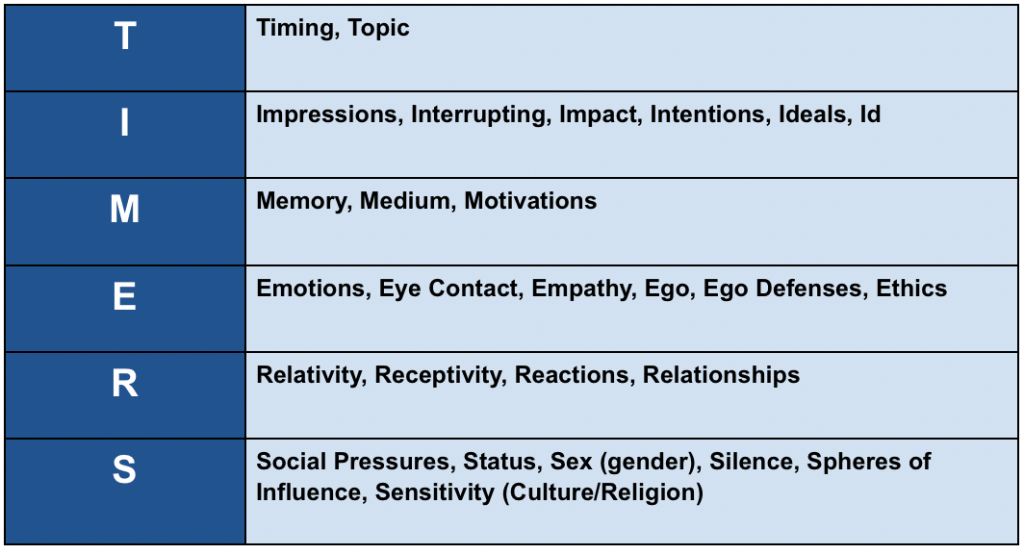

After introducing the TIMERS framework Caldicott asked Dr. Connors and the others in the class to use these prompts to consider why they had been perceived as uncivil. As they jotted down notes on the TIMERS worksheet, they were urged to add other elements they found helpful. “T” might stand for Tension or Topic, as well as Timing. “I” could trigger reflections about Impact or Intentions.

One of the concepts Caldicott discussed in presenting the TIMERS framework was “parallax,” the idea that your location affects where objects appear to be located. Look at your thumb with one eye closed, then switch eyes. Because of the distance between your eyes, your thumb seems to jump from one spot to another. In the same way, said Caldicott, a person in another position, literally or figuratively, might well view a situation differently than you do.

For the first time, Dr. Connors realized that Andrew and Ms. Forbes were viewing the encounter that day from their own points of view. Andrew’s different perspective might have allowed him to see things, like Ms. Forbes’ anxiety, that Dr. Connors missed. If so, Ms. Forbes would have viewed the nurse’s comment not as an intrusive interruption, but as a welcome intervention. This realization led Dr. Connors to reconsider the entire encounter.

By the time he had completed the TIMERS worksheet, he had added a couple of new elements under “E” and “S” and gained a whole new understanding of what had happened.

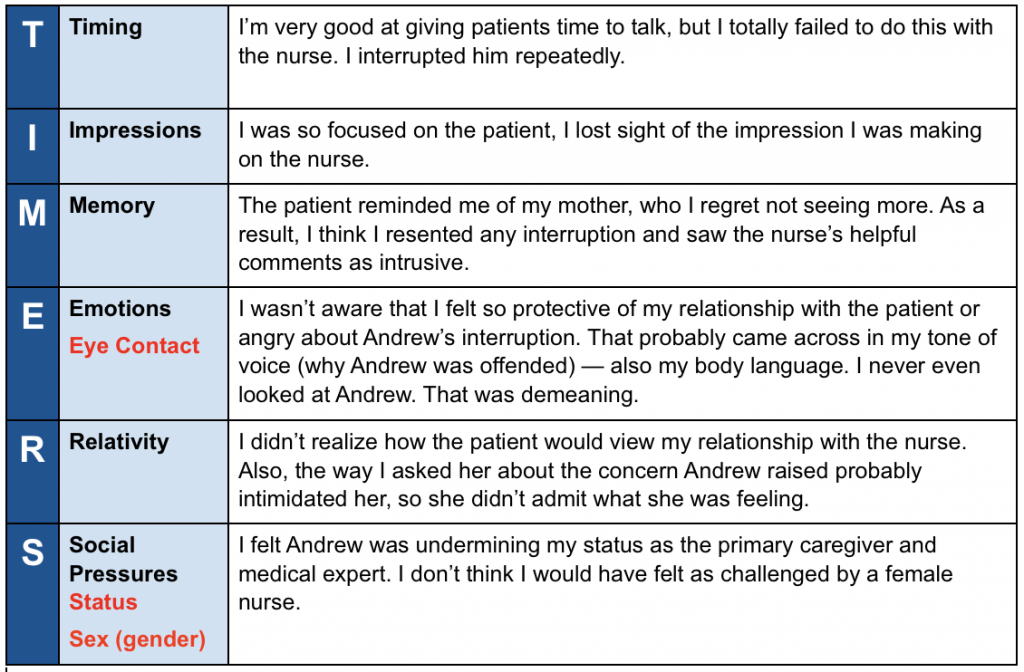

Here’s what he wrote:

As he discussed these perceptions with others in the class, Dr. Connors began to see a larger pattern. As the hospital recognized with the commendation, he was generally good with patients (although now he wondered how often he had missed clues as he did with Mrs. Forbes). He always made eye contact, gave people time to talk without interruption, and did his best to ensure that they did not leave with any unanswered questions or misconceptions. But as Andrew’s complaint made clear, Dr. Connors did not use these same skills with staff. He tended to think of himself as superior to the nurses and others he worked closely with and took them for granted.

Turning insights into action

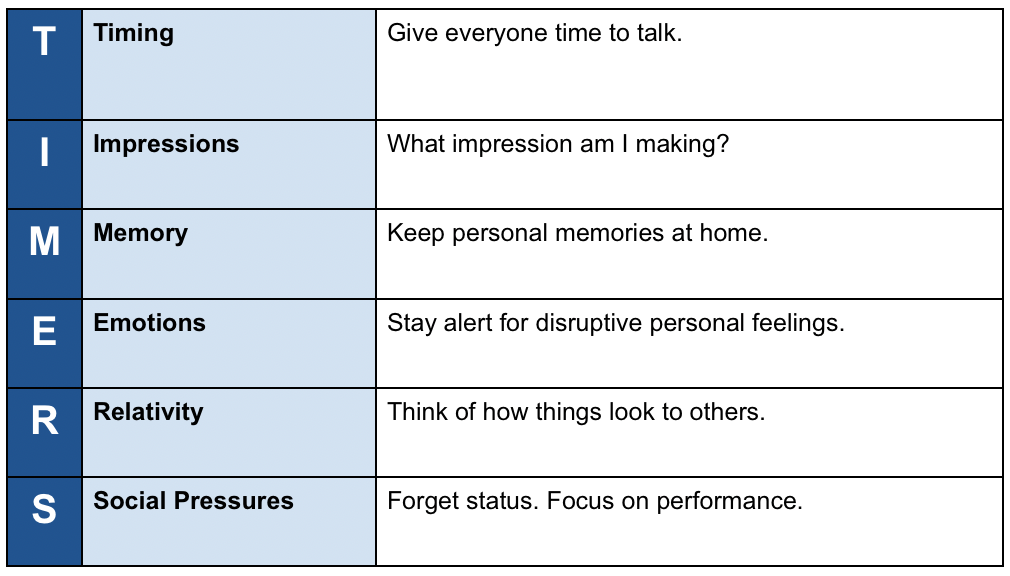

At the end of PBI Education courses, participants use what they have learned about themselves in class to create “Protection Plans” that can help them avoid problems in the future. Caldicott suggested that once the participants in the Civility and Communication course had completed their Plans, they might think of using TIMERS as a mnemonic to keep key elements in mind during the day. Andrew’s list looked like this:

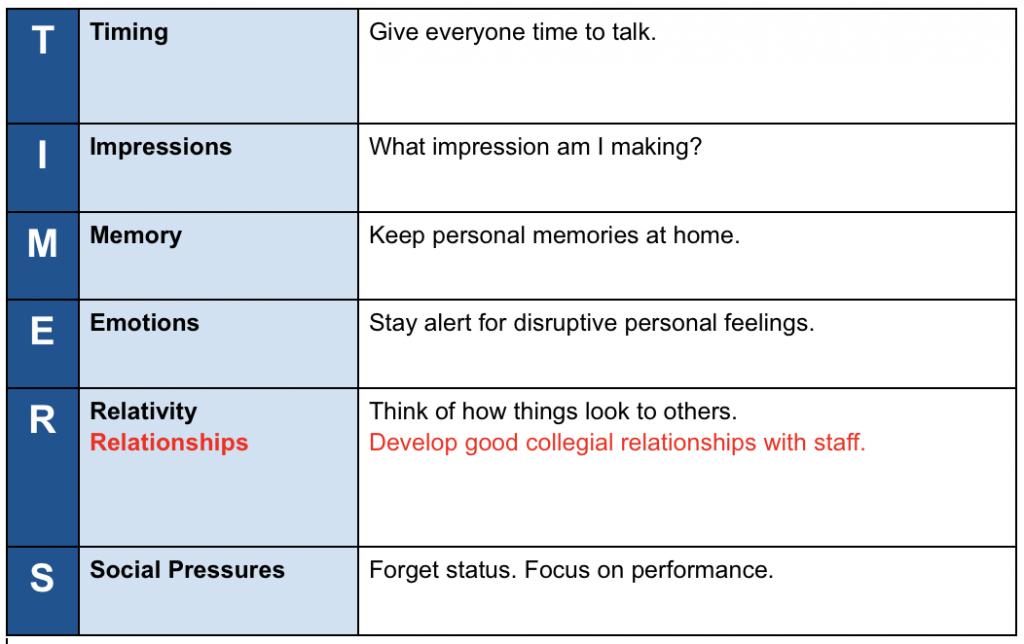

For 12 weeks following the Civility and Communication course, Andrew and the other participants joined in one-hour weekly conference calls led by Caldicott. About midway through these calls, Andrew brought up a new concern. It wasn’t enough to just stop taking nurses and others for granted. He realized he needed to treat them as colleagues. After some thought and discussion, he decided to update his Protection Plan and TIMERS list:

As a reference, below is a TIMERS table with a few more elements to consider when taking a personal inventory of one’s own communication style.

Armed with his TIMERS and the broader perspective he had gained from the course, Dr. Conners was able to continue practicing with his current employer without further incident. Something unexpected did happen, though, in the months following the course. He found that by intentionally focusing on building relationships with the clinicians around him, he actually enjoyed his work more. He realized he had come to find a deeper sense of belonging in his organization and within his healthcare team.

Additional Resources

For more information about improving communication, especially with patients that present challenging behaviors, we recommend our online Managing Clinician-Patient Conflicts Course.

Issues addressed in the course include:

- Internal and external factors that cause communication breakdowns

- Personality disorders: understanding them and working with them

- Strategies for de-escalation

- Managing defensive behavior in the clinician or patient

- Managing non-compliant behavior

Click here to learn more about this course.

Additional Blogs from PBI Education:

What Is Civility and Why Does It Matter?

WARNING: Mistaken Assumptions Can Be Hazardous to Your Patients’ Health

TIMERS© 2019 PBI Education