What Is Civility and Why Does It Matter?

What Is Civility and Why Does It Matter?

Numerous studies have shown that effective teamwork improves patient outcomes, increases hospital efficiency, and reduces burnout among doctors and nurses. It’s not surprising. In health care, as in virtually every other field of endeavor, it has been clear for some time that high-functioning teams outperform individuals. Strong teams generate more ideas, catch more mistakes, and can access more expertise than individual team members ever could on their own.

But of course not all teams are effective. In fact, according to a 2016 article in the AMA Journal of Ethics, “teamwork failures (e.g., failures in communication) account for up to 70-80% of serious medical errors” and “are a contributory factor in 61% of sentinel events” (i.e., unanticipated deaths or serious injury to patients). Other studies have found that poor teamwork causes virtually all the ills good teamwork is known to remedy, from clinician burnout to hospital inefficiency.

Teams fail for many reasons, but the most common obstacle to success is incivility, the failure to respect and value those we disagree with. Too many of us today equate civility with superficial good manners. In polite society we are taught it is best to avoid areas of disagreement and say nothing if we have nothing nice to say. Such risk avoidance is in fact the antithesis of civility.

The Institute for Civility in Government offers the following definition:

“Civility is about more than just politeness, although politeness is a necessary first step. It is about disagreeing without disrespect, seeking common ground as a starting point for dialogue about differences, listening past one’s preconceptions, and teaching others to do the same.”

It is this willingness to value what others think that allows team members to benefit not just from each other’s expertise, but also from one another’s concerns and doubts. Civility establishes a zone of psychological safety, within which, “People feel they can ask a ‘dumb question,’ stop action when they identify a safety problem, or challenge a superior without fear of retaliation, humiliation, or disregard,” note the editors of Collaborative Caring: Stories and Reflections on Teamwork in Health Care.

Civility is as rare as it is difficult. While nearly everyone endorses the idea of teamwork and civility, very few are able to translate it into concrete action. It’s hard enough to suppress your disdain for ideas you don’t agree with; true civility demands you put aside your condescension and seriously consider whether or not the ideas have value. Rather than simply gritting your teeth and smiling politely when someone criticizes you, civility asks you to actually entertain the possibility that the criticism they offer is valid.

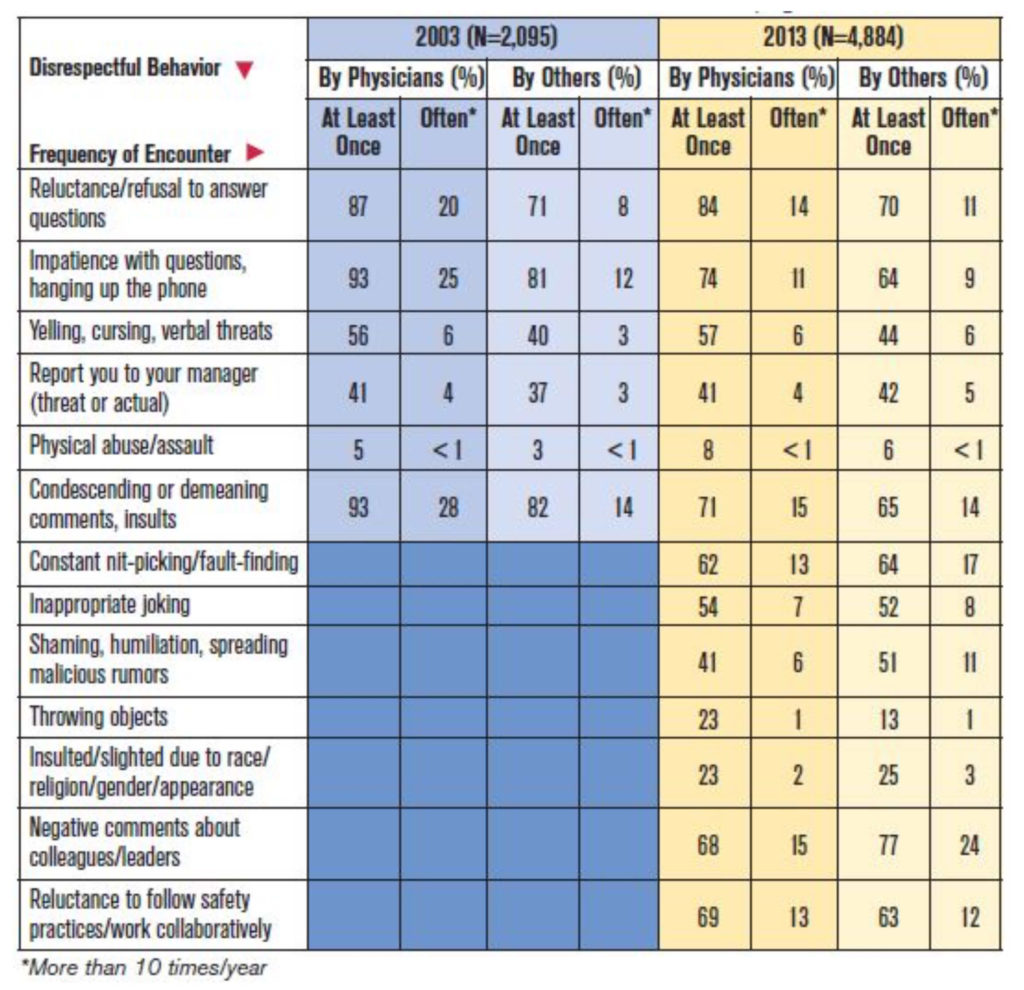

Such genuine civility is hard to find anywhere, least of all in health care. Despite years of research and bold initiatives, blatant disrespect and disruptive behavior are as prevalent as ever, according to surveys that the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) conducted in 2003 and 2013. As the accompanying chart shows, little changed in the ten years between the surveys. Physicians and others continued hanging up on people, yelling, cursing, insulting, and generally making life miserable for those they worked with. And this list doesn’t even include passive-aggressive behaviors (as when someone repeatedly fails to do what they say they will) and non-verbal slights (such as sighing or eye-rolling).

Incivility destroys more than just teamwork. In fact, rampant incivility is responsible for many of the problems plaguing modern health care.

- Disrespectful behavior chills communication and collaboration. Surveys in 2003 and 2013 by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) confirmed what other research has found: people avoid those who belittle them, often with disastrous consequences for patients. Most commonly, nurses and others intimidated by offending physicians refrain from offering relevant information, raising questions, or asking for clarifications. In 2013, for instance, 33% of those surveyed who had concerns about a medication order assumed it was correct rather than interact with an intimidating prescriber. The potential for disaster is clear and numerous cases of serious harm have been documented.

- Incivility degrades individual contributions to care. Disrespect is more than unpleasant. Mounting research shows rudeness can cause employees to be chronically distracted, less productive, and less creative. It causes a host of disabling emotions—including fear, anger, shame, confusion, uncertainty, isolation, self-doubt, and depression—not to mention physical ailments, such as insomnia, fatigue, nausea, and hypertension. All of which diminishes the victim’s ability to think clearly and make sound judgments.

A 2017 study, published in the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, found that doctors and nurses in neonatal intensive care units who were scolded by an actress playing the mother of a sick infant, performed much more poorly than those who were not mistreated — even misdiagnosing the infant’s condition. “The results were scary,” an author of the study told the Wall Street Journal. “The teams exposed to rudeness gave the wrong diagnosis, didn’t resuscitate or ventilate appropriately, didn’t communicate well, gave the wrong medications, and made other serious mistakes.”

- A hostile work environment lowers morale and causes burnout.When people are treated badly, morale plummets. One study found increased incivility at work had personal-life implications, such as a drop in marital satisfaction. Rather than endure such a toxic environment, healthcare professionals start missing work. Some resign and a certain percentage (no one knows how many) decide to leave the profession.

- Patients suffer directly when treated disrespectfully. Even more than their caregivers, patients are cowed into silence by physicians who treat them dismissively or with open hostility. They hesitate to ask pertinent questions, avoid correcting mistakes, and fail to share critical information.

Perhaps worst of all, incivility begets more incivility. In a 2016 study, researchers found that individuals insulted earlier in the day tend to strike back at coworkers later on. In a recent article in the Washington Post Trevor Foulk, of the University of Maryland, said, “When it comes to incivility, there’s often a snowballing effect. The more you see rudeness, the more likely you are to perceive it in others and the more likely you are to be rude yourself to others.”

The good news is that civility can be learned. “Don’t assume everyone instinctively knows how to be civil; many people never learned the basic skills,” writes Christine Porath in a recent Harvard Business Review article. She mentions several leading-edge companies that now offer formal civility training, including the National Security Agency, Microsoft and a hospital in Los Angeles, where employees are trained to watch for unreported instances of incivility and doctors are held accountable for the consequences of any bad behavior they fail to report.

Whether you participate in an institutionally-sponsored program, take a course or work individually with a therapist or coach, the first step towards improving civility is often the hardest, accepting your own need to improve. “It’s hard for us to consider that we may be a part of the problem,” says Daniel Buccino, director of the Johns Hopkins Civility Initiative. In fact, he notes, “Studies of this are pretty consistent: 95% of Americans think that incivility is a problem—in the world, the U.S., and their lives. And yet 95% of people say that they are always or mostly civil.”

PBI Education’s course, “Elevating Civility and Communication in Health Care,” begins by asking participants to identify moments when they behaved disrespectfully to someone and to consider the factors that influenced their behavior. “It’s a useful exercise for everyone,” says PBI Education Founder Stephen Schenthal, MD. “You begin reducing your “Incivility Potential” the moment you start asking yourself some fundamental questions,” he explains.” Among the questions Schenthal suggests:

- How receptive are you when a teammate offers a new idea?

- How do you respond to constructive criticism?

- Judging by how others respond to your suggestions, how respectful would you say you are?

View Other Posts

- Summer School: Reduce Stressors, Avoid Burnout

- Don’t Wait Until it is Too Late: How a Personalized Protection Plan© Decreases Violation Potential

- The What, Why, When, and How of Remedial Educational Interventions

- Revisiting Moral Courage as an Educational Objective

- If It Isn’t Documented, It Didn’t Happen