The Growing Importance of Cultural Competency

The Growing Importance of Cultural Competency

If you’ve ever had to see a doctor while traveling abroad, you know how trying it can be. Even if you and the doctor are able to communicate in a common language, one or both of you is apt to misspeak or misunderstand precisely what the other is trying to say. Less obvious, and all the more disconcerting, are cultural misunderstandings. The physician who is trying to put you at ease may unwittingly come across as pushy and overly familiar, while your innocent questions may strike the doctor as interfering and mistrustful.

Physicians in this country face similar challenges every time they see a patient from another culture. Patient populations today are more diverse than ever before, and doctors and nurses are continually challenged to care for patients who do not share their cultural values or assumptions. In response, numerous programs and publications have been developed to help U.S.-trained physicians improve their “cultural competency,” the ability to care for patients from different geographic, ethnic, racial, religious or social groups.

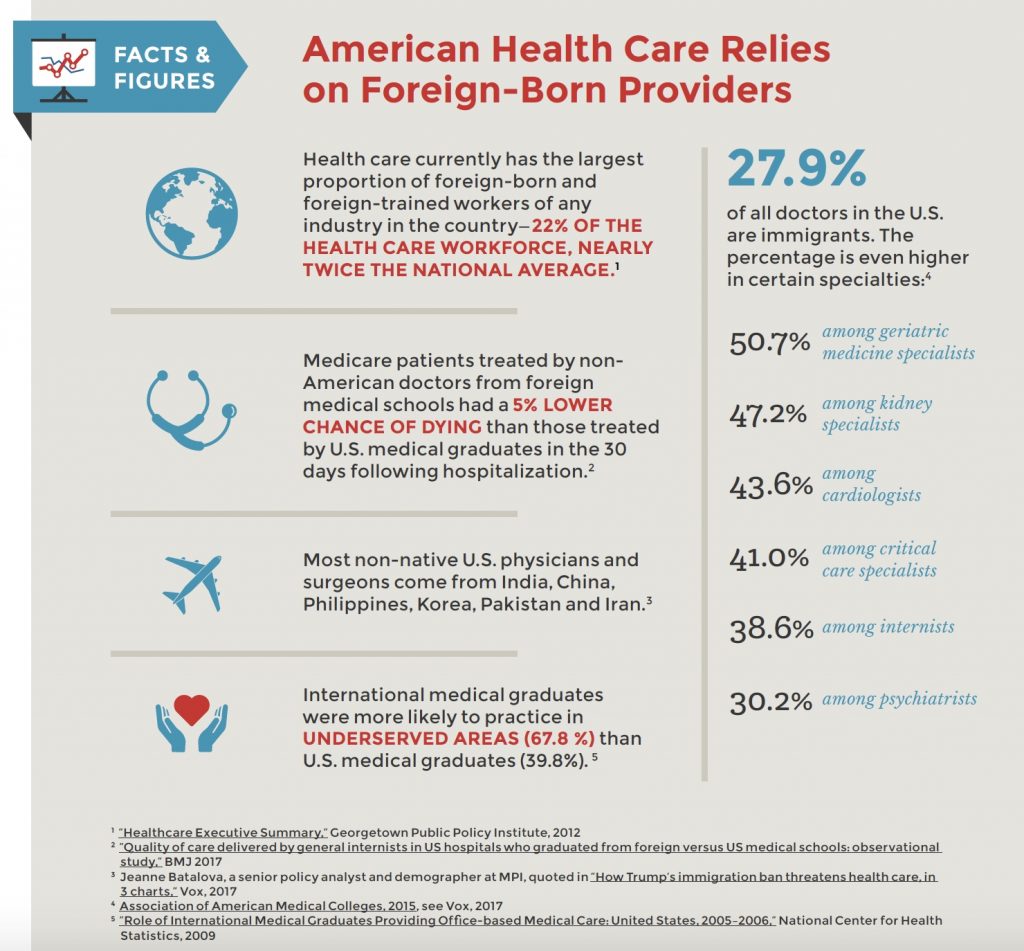

Less attention has been paid to the challenges confronting foreign-born physicians. These international medical graduates (IMGs) now account for more than a quarter of all U.S. physicians and many prominent health care officials have noted the increasingly important role IMGs play in meeting the country’s demand for medical care. Yet while these providers are well-trained and skillful practitioners (see Facts and Figures below), many find themselves unprepared for cultural differences that can jeopardize their careers. As long ago as 2012, a program aimed at helping address the problem noted, “International Medical Graduates are more likely to be involved in complaints… and differences in culture and consulting style are suggested to be the cause.”

In recent years, PBI’s courses have included a growing number of health care professionals whose cultural myopia has blinded them to unintended boundary violations. Sometimes the offense is committed by an American physician who is insensitive to the expectations of patients from other countries. Other times, it’s foreign-born doctors whose cultural assumptions clash with the expectations of U.S. patients.

Among a wide range of issues, three are particularly common:

1. Unintended sexual harassment

In many parts of the Middle East, Latin America, Africa and southern Europe, people are far more comfortable with physical contact than most Americans are, especially in a medical setting. One Latin American physician who had been practicing in this country for years without incident, hugged a female patient who he thought needed comforting. Having done the same thing many times before, he was astonished when the woman claimed that he touched her breast and filed a complaint.

In another case, a Middle Eastern surgeon had routinely hugged nurses he worked with as a way of saying thank you. When he began practicing in the U.S., many of his coworkers tolerated his expressions of gratitude. But several female nurses felt uncomfortable and resisted what they considered improper touching. When the surgeon continued the practice, apparently oblivious to their discomfort, they filed charges.

The situation is reversed when U.S.-born doctors treat patients from cultures where physical contact between men and women is less tolerated than it is here. More than one religion forbids contact between members of the opposite sex who are not related. One physician failed to take this cultural sensitivity seriously enough. When a female patient’s husband failed to accompany her as he had for every previous appointment, the physician tried to conduct the exam as usual. The woman was both offended and frightened and filed a complaint.

2. Blurring personal and professional boundaries

While American patients generally understand that there are legitimate medical reasons for a doctor to ask about specific aspects of their personal lives, they resent any intrusion that seems to cross the line. Where that line is, however, is often culturally determined. One physician was accustomed to discussing matters of faith with patients in her home country. Both she and her patients felt that their spiritual and physical health were intimately related. But once the doctor started practicing in the U.S., where most people view religion as intensely personal, her patients took offense and filed charges when she asked what they considered intrusive questions about their religious beliefs.

Other physicians new to this country treat virtually all their patients, especially those from their own culture, as if they were relatives. Whether they are members of a close-knit Hispanic neighborhood or a first-generation Korean community, these doctors tend to have trouble saying no to people they regard as brothers and sisters. Rather than risk seeming rude, doctors in such situations have loaned patients large sums of money, put them up in their homes, accepted gifts and offered them employment—all against the explicit policies of the office they worked in.

3. Confusing collaboration with insubordination

Fifty years ago patients and staff in this country were expected to accept the authority of physicians and to follow their instructions without question. Today, patients often come to appointments with information they have gathered online, ready to participate in any decisions about their care. And staff are generally encouraged to voice concerns and share opinions.

Doctors trained in a more hierarchical society often react to this collaborative culture much as a physician from 1950 would: they are outraged. They feel disrespected by patients who ask questions and raise concerns, and sometimes react angrily to what they consider a lack of appropriate deference. The problem can be even more pronounced in dealings with colleagues—nurses and other medical professionals—whom these doctors tend to treat dismissively, if not with overt hostility. Needless to say, such behavior leads to complaints and often to disciplinary action.

With the recent furor over immigration, many leaders in the field of health care have recently pointed out how valuable foreign-born physicians are to this country. Immigration policies alone are not enough however. As both the patient population in the U.S. and the medical profession grow more diverse, more needs to be done to help health care providers gain the cultural competency they need to be effective and successful.

View Other Posts

- New Data Suggest Remedial Courses Reduce Recidivism

- Summer School: Reduce Stressors, Avoid Burnout

- Don’t Wait Until it is Too Late: How a Personalized Protection Plan© Decreases Violation Potential

- The What, Why, When, and How of Remedial Educational Interventions

- Revisiting Moral Courage as an Educational Objective