PBI Field Guide to the Legal Landscape

PBI Field Guide to the Legal Landscape

Before the first day of class even begins, physicians and other professionals taking a PBI course are asked to review and write-up the state laws that are relevant to their violation, as well as those sections of both the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics and the ethical code of their own specialty. For many, this will be their first encounter with the rules their license obligates them to follow.

The narrow focus on the assignment offers class participants just a glimpse of the larger legal landscape in which they practice. Many participants say after the class that they might have avoided their violation if they had taken a more serious view of regulations earlier in their career.

Easier said than done. The legal landscape can seem a tangle of intertwining state and federal laws, board policies and orders, Medicare rules and professional codes of ethics, which is why we’ve put together this brief field guide. *Please keep in mind that this is merely an overview. It’s up to you to familiarize yourself with the laws and regulations of your individual state. And if you have any questions, be sure to consult an attorney familiar with the field.

PROFESSIONAL ETHICS

THE HIPPOCRATIC OATH: Hippocrates planted the first ethical seed for physicians more than 2,500 years ago. Some physicians probably never make it past the oath’s opening reference to ancient gods and goddesses, but the brief text remains surprisingly relevant today, touching on abortion and euthanasia, for instance, and on sexual misconduct and confidentiality. It reads in part,

“I WILL ABSTAIN FROM ALL INTENTIONAL WRONG-DOING AND HARM, ESPECIALLY FROM ABUSING THE BODIES OF MAN OR WOMAN, BOND OR FREE. AND WHATSOEVER I SHALL SEE OR HEAR IN THE COURSE OF MY PROFESSION, AS WELL AS OUTSIDE MY PROFESSION IN MY INTERCOURSE WITH MEN, IF IT BE WHAT SHOULD NOT BE PUBLISHED ABROAD, I WILL NEVER DIVULGE, HOLDING SUCH THINGS TO BE HOLY SECRETS.”

THE AMA’S MEDICAL CODE OF ETHICS is more wide-ranging. Recently updated and reorganized, the AMA code consists of nine clear and concise principles, supplemented by 11 chapters’ worth of opinions. Since more than one state law obligates physicians to adhere to the AMA code, and all states expect them to, it is not a document one should ignore.

Specialty codes of ethics: In addition to the AMA Code of Ethics, every medical specialty—from Anesthesiology to Urology—has its own ethical code, dealing with issues that are relevant to those who are certified. Again, states expect specialists to live up to these codes.

FEDERAL LAW

U.S. Controlled Substances Act regulates the manufacture, importation, possession, use and distribution of those substances specified in one of the act’s five schedules. The schedules are based on the substance’s medical use, potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability, and the act changes over time as substances are added, deleted or moved from one schedule to another. A violation of this act almost always prompts both federal and state action.

Medicare/Medicaid Fraud and Abuse Laws: According to the Office of the Inspector General of the US Department of Health and Human Services, there are five fraud and abuse laws that physicians should pay special attention to, “not only because following them is the right thing to do, but also because violating them could result in criminal penalties, civil fines, exclusion from the Federal health care programs, or loss of your medical license from your State medical board.” The five laws are:

- FALSE CLAIMS ACT: It is illegal to submit claims for payment to Medicare or Medicaid that you know or should know are false or fraudulent.

- PHYSICIAN SELF-REFERRAL LAW (Stark Law) prohibits physicians from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or Medicaid from entities with which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial relationship,

- ANTI-KICKBACK STATUTE: In the Federal health care programs, paying for referrals is a crime. The statute explicitly rules out taking money or gifts from a drug or device company or a durable medical equipment (DME) supplier, even if the physician would have prescribed that drug or ordered that wheelchair in any event.

- EXCLUSION AUTHORITIES: Excluded physicians may not bill directly for treating Medicare and Medicaid patients, nor may their services be billed indirectly through an employer or a group practice.

- CIVIL MONETARY PENALTIES LAW authorizes the imposition of CMPs for a variety of health care fraud violations. Penalties range from $10,000 to $50,000 per violation. CMP also may include an assessment of up to three times the amount claimed for each item of service or up to three times the amount of remuneration offered, paid, solicited, or received.

The Medical Practice Act (HIPPA) protects the privacy of patient health information. It sets boundaries on the use and release of health records and holds violators accountable, with civil and criminal penalties that can be imposed if they violate patients’ privacy rights. As with the Controlled Substances Act, most state laws refer to HIPPA and/or include the same restrictions.

STATE LAW

MEDICAL PRACTICE ACTS: Every state has its own Medical Practice Act (MPA), which covers topics such as the qualifications for licensure, the practice of medicine and the structure and procedures of the board itself. These statutes, which generally reflect and/or refer to federal laws and various codes of ethics, cover both clinical violations of standards of care and non-clinical matters, such as fraud, improper relationships with patients, and substance abuse.

In addition to the objective criteria listed in each state’s MPA, there is often a catch-all category that allows the board to make subjective judgments about what is and is not professional conduct. Washington’s MPA refers, for instance, to “the commission of any act involving moral turpitude, dishonesty or corruption, or relating to the practice of the person’s profession, whether it constitutes a crime or not.”

Although MPA statutes are generally folded into the state’s overall legal code—usually in the Business and Professional section—and go by different names (Mississippi has an Administrative Code, while Washington has its Uniform Disciplinary Act), each state’s medical board posts all the relevant statutes on its website. Also available on board websites are “board orders,” which record the more subjective judgments the board has made regarding what it considers professional misconduct. Together, the MPA and board orders are must reading for anyone who values their license.

These are lengthy documents, often over 100 pages, but they are essentially lists of short entries and easily scanned.

A FEDERAL SYSTEM WITHOUT THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

INTER-STATE ENFORCEMENT OF DISCIPLINE:

To prevent physicians from escaping disciplinary actions by simply moving to another state, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) created the Physician Data Center, which the federation describes as, “A comprehensive data repository that contains information about the more than 870,000 actively licensed physicians in the United States, as well as board disciplinary actions dating back to the early 1960s.” Boards use this database to vet new applicants for licensure and, “The Data Center’s Disciplinary Alert Service pro-actively alerts all states in which a disciplined physician is licensed within 24-48 hours after a disciplinary action taken by one of those states has been reported.” It’s up to each state to decide how to respond—whether to mirror the discipline, for instance, or perhaps take stronger measures.

INTER-STATE LICENSING FOR TELEMEDICINE:

Telemedicine makes it possible for patients to be “seen” by a doctor even if there’s no physician available to them locally. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for the patient and doctor to be on opposite sides of a state line, which means the physician has to be licensed in both states. Under current law, a physician has to go through the often lengthy licensing process state by state.

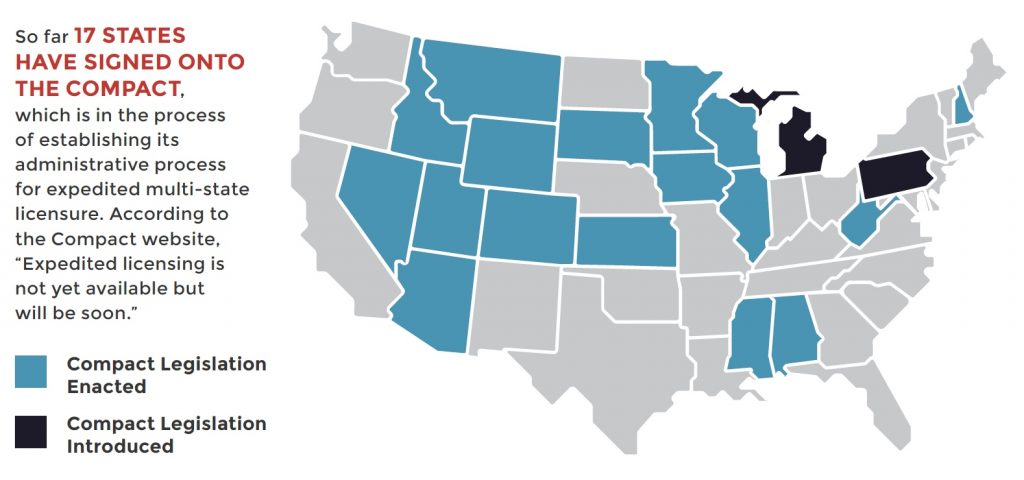

In 2013 FSMB organized a team of state medical board representatives and experts from the Council of State Governments (CSG) to draft an Interstate Medical Licensure Compact — a new licensing option under which qualified physicians seeking to practice in multiple states would be eligible for expedited licensure in all states participating in the Compact.

1 | COMPLAINT PROCESSED

STAFF REVIEWS ALL COMPLAINTS ON A REGULAR BASIS. Preliminary information on each complaint is referred to commissioners, who decide whether or not the complaint falls within the board’s jurisdiction. If not, the complaint is referred to the proper authority.

2 | CASE PRIORITIZED

THE BOARD DETERMINES IF THERE IS AN IMMINENT THREAT TO THE PUBLIC. If so, it immediately suspends the physician’s license and orders the physician to cease seeing patients until a hearing can be held.

3 | INVESTIGATION PROCEEDS

INVESTIGATORS INTERVIEW THE PHYSICIAN AGAINST WHOM THE COMPLAINT HAS BEEN MADE, THE COMPLAINANT AND ANY WITNESSES WHO MIGHT BE HELPFUL. The investigators also gather physical evidence, including medical and pharmacy records if necessary. When the investigation is complete, a full report is given to the commissioners, along with all the evidence gathered.

4 | REVIEW OF INVESTIGATION FINDINGS

THE COMMISSIONERS REVIEW THE INVESTIGATION FINDINGS, WITH THE HELP OF BOARD-CERTIFIED SPECIALISTS IF NEEDED. If they do not find sufficient evidence of a violation, the case is dismissed. If they believe that a violation has been committed, they decide whether to proceed with informal discipline, such as a warning or reprimand, or to a formal statement of charges. Relatively few cases result in formal charges.

5 | FORMAL CHARGES ANNOUNCED

IF THE BOARD DECIDES TO FILE CHARGES, A LEGAL DOCUMENT WILL BE ISSUED NOTIFYING THE PHYSICIAN. At this point, the physician can choose to either answer the charges or request a settlement conference. In the latter case, the physician and their attorney meets with the representatives of the board to discuss options. If they reach an agreement, and the board accepts it, board orders—generally known as consent decrees—are issued.

If an agreement is not reached or the physician chooses to contest the charges, a formal hearing, known as an administrative tribunal, is held. Such hearings are similar to civil trial, but there are important differences. Witnesses are questioned by both sides and evidence is presented, for example, but a health law judge presides over the proceedings and instead of a jury, board commissioners hear the case. Once all the testimony is completed, the commissioners go into a closed-door session and return with a judgment.

The disciplinary options are the same whether there is a hearing or a settlement. The reason so many physicians prefer the settlement route is that it’s quicker, easier and less expensive. One disadvantage of a consent agreement is that it precludes the possibility of an appeal, since both parties agreed to the judgment ahead of time. In the case of a hearing, the physician can appeal the board’s decision in civil court, although board decisions are rarely reversed.