How Doctors Learn (and Don’t Learn) About Professionals Boundaries

How Doctors Learn (and Don’t Learn) About Professionals Boundaries

It all starts with personal boundaries

Boundaries are easiest to spot when they are violated. Few of us are pay much attention to our personal space until someone intrudes on it, and privacy generally becomes an issue only when someone betrays a confidence.

In fact, one of the ways we first learn about boundaries is by testing them. Whether it’s a toddler defying instructions to stay close, a six-year-old refusing to brush her teeth, or a teenager coming home later than he said he would—all are testing boundaries. What they learn from these early experiments has a great deal to do with how the adults in their lives respond.

Small children test boundaries as they work to figure out their relationship to the world around them and how to handle new, powerful emotions. They are teasing out just how far they can go, and how far they want to go. When parents set clear boundaries that respect their children’s growing competence, they teach their offspring something important about their place in the world: “Your power has limits and there are times when you have to restrain yourself to accommodate others.” Toddlers may feel angry and resentful, but once the tantrum fades, they feel safer and less anxious knowing that there are adults who will set limits that keep them safe and help them manage those overwhelming feelings.

Such testing continues throughout childhood and adolescence. Older children and teens learn a great deal about boundaries by watching how their parents behave. If a parent always puts their own needs ahead of their child’s, their children are likely to feel powerless and resentful, and to learn that such self-centeredness is the only way to get what they want. At the other end of the spectrum, parents who always put others’ needs ahead of their own teach children that one’s own feelings are of little importance and that the only way to measure up is to be as self-sacrificing as they are.

The situation is seldom so simple, of course. And as important as early testing and parental models are, we never stop learning about boundaries, as we continue to observe others—authority figures, sweethearts, colleagues, fictional characters—setting or failing to set limits.

If we’re lucky, this never-ending education teaches us how to respect other’s boundaries and how to set boundaries for ourselves. We learn, too, that static, rigid boundaries can be as unhelpful as boundaries that are too amorphous and elastic. Healthy boundaries, like healthy cell membranes, regulate effectively by responding dynamically to changing environments.

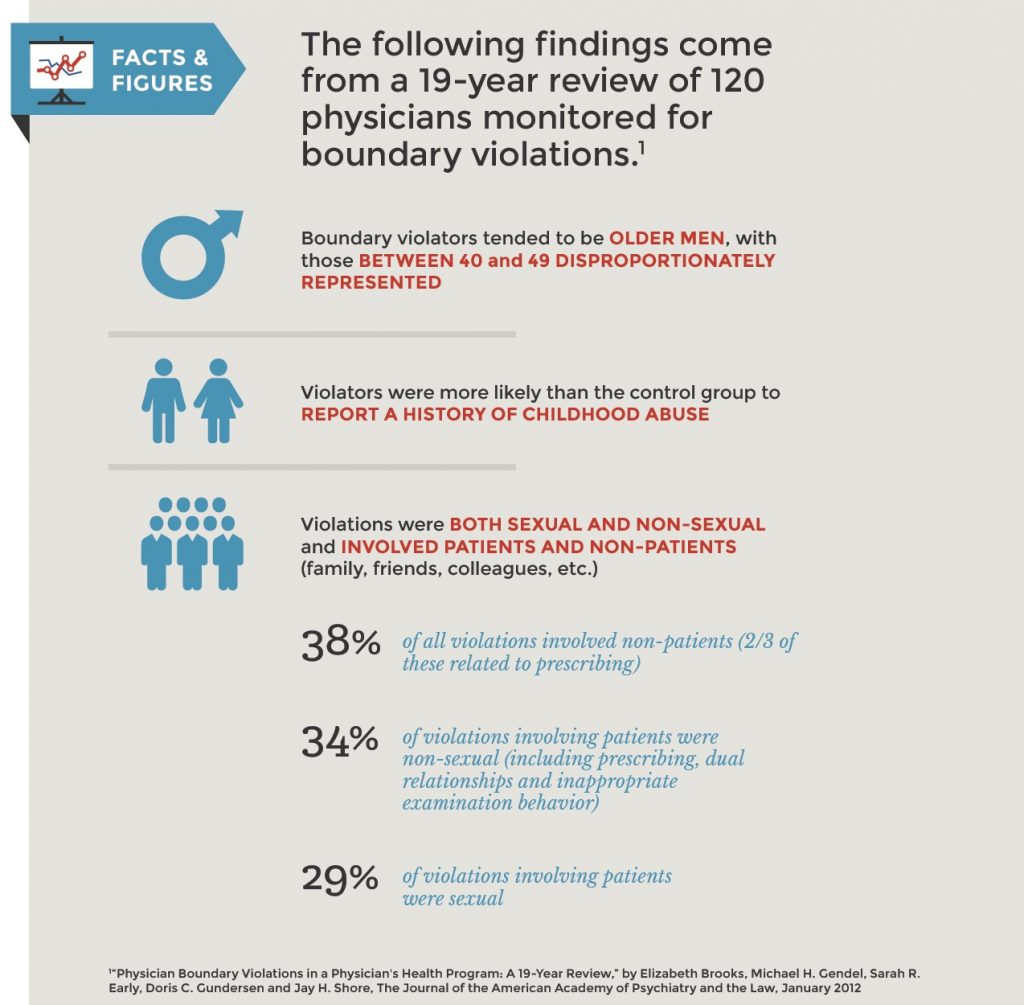

How well we learn about boundaries is important in both our personal and professional lives. The insecure adult who has never learned to say “no” becomes the doctor who in more interested in pleasing her patients than using her own best clinical judgement. The adolescent who learned to manipulate others for his own ends, becomes the predatory physician who misuses his power over vulnerable patients.

How we don’t learn about professional boundaries. Even the best adjusted professional, with a mature grasp of personal boundaries, does not enter the profession with a clear understanding of professional boundaries. The doctor-patient relationship is unlike other relationships and the responsible physician must learn the unique boundaries that govern it. Unfortunately, as mentioned in this issue’s editorial, the subject is given scant attention in medical school. For the most part doctors learn about professional boundaries in much the same way they learned about personal boundaries growing up: by observing how others behave.

Needless to say, it is difficult to learn the importance of establishing and respecting boundaries when those around you routinely disregard them. Harder still when schools, hospitals and private practices shy away from disciplining even flagrant violators, especially if they are a source of significant revenue for the institution. A few years ago, the head of cardiology at an Ivy League medical school made advances to a female researcher, who turned him down. The cardiologist took his frustration out on her fiancé (now husband), whom he supervised. When the medical school failed to take action, the couple was forced to file a complaint with the university Committee on Sexual Misconduct. Even then, it was not until the New York Times broke the story that the offending physician was forced from his position.

It’s impossible to judge how common such situations are, since many cases are buried or settled with as little publicity as possible. But it’s not only major incidents like this one that influence what young doctors learn about appropriate and inappropriate behavior. A recent survey in the U.K. revealed that medical students frequently witnessed their instructors behaving in ways they knew were inappropriate. According to a report in the BBC, “Some of the testimonies gathered from medical students are jaw-dropping.”

- One patient was told by a physician, “You shouldn’t even be here. You’re so fat I shouldn’t even have considered you for surgery.”

- In another instance, a physician called out to a female student, “You there, the decoration, why did you even come to med school? Do you have a brain in your pretty head?”

“Students pick up these subtle patterns of behavior and they come to learn this is how things are done around here, this is how work is done,” noted Dr. Lynn Monrouxe of Cardiff University. “The small subtle interactions that happen day in, day out—not necessarily the big, shocking, news-grabbing headlines—It’s the things that can’t be counted that really count.”