Getting to the Bottom of the Opioid Epidemic

Getting to the Bottom of the Opioid Epidemic

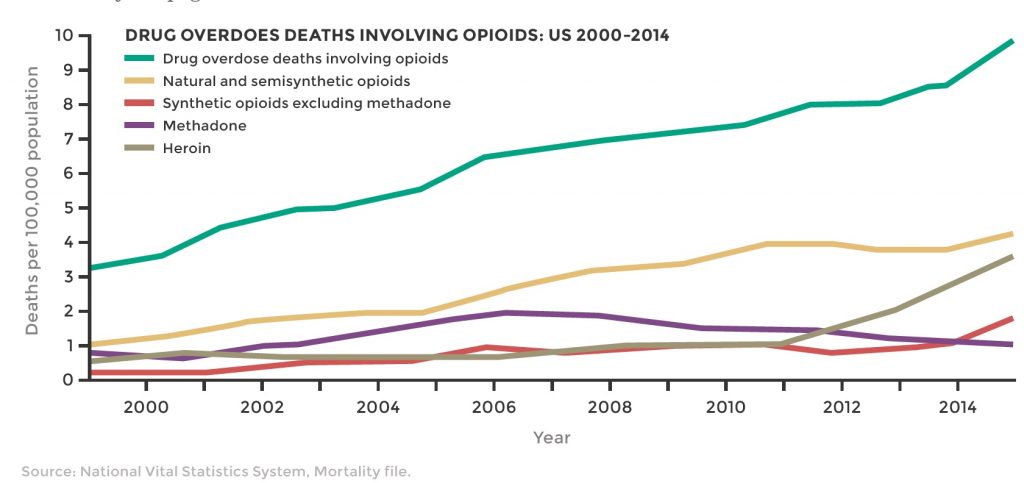

The facts seem all too clear. In 1999, 8,200 people died from opioid overdose. Fifteen years later, that number had more than quadrupled to 33,091. And the trend has been accelerating (see chart). Today, more people die of opioid overdose In just two years than died during all of the Vietnam war.

According to many, the cause of the opioid epidemic is just as clear. “We now know that prescription opioids are a driving factor in the 15-year increase in opioid overdose deaths,” notes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Since 1999, the amount of prescription opioids sold in the U.S. nearly quadrupled, yet there has not been an overall change in the amount of pain that Americans report.”

If you assume the problem is doctors writing too many prescriptions for opioids, the solution is painfully obvious: just clamp down on prescribers. That is precisely what an increasing number of states are doing, according to Jennifer P. Schneider, MD, PhD, a nationally recognized expert in the management of chronic pain with opioids and a prolific author on the subject.

“They are telling primary care physicians that they can’t prescribe more than a low dose, typically the starting point for treatment, without consulting a pain specialist.” But Schneider points out there are nowhere near enough pain specialists to make this practical. “That’s why it’s such a useless and destructive approach,” she says, “because the primary care doctors (who are generally the ones prescribing opioids) just say, ‘I’m not going to prescribe this stuff anymore.’ And that means millions of legitimate chronic pain patients will be deprived of effective treatment.”

But what if the driving force behind the epidemic is not simply irresponsible over-prescribing? What if, contrary to the CDC’s assertion, there has been an increase in the amount of pain Americans are experiencing?

That is the conclusion suggested by Princeton economists Angus Deacon and Anne Case. In 2015, the husband-and-wife team discovered a startling reversal in the life expectancy of middle-aged white Americans with less than a high school education. After more than a century of decline, the mortality rate of this group began to increase 15 years ago and has been climbing ever since. The immediate causes were clear, Deacon told NPR. “We knew suicides were going up rapidly, and that overdoses mostly from prescription drugs were going up, and that alcoholic liver disease was going up. The deeper questions were why those were happening.”

The reason, the economists propose, has been a collapse in the labor market. Deacon, who won the Nobel Prize in 2015, explains it this way:

“If you go back to the early ’70s when you had the so-called blue-collar aristocrats, those jobs have slowly crumbled away and many more men are finding themselves in a much more hostile labor market with lower wages, lower quality and less permanent jobs. That’s made it harder for them to get married. They don’t get to know their own kids. There’s a lot of social dysfunction building up over time. There’s a sense that these people have lost this sense of status and belonging. And these are classic preconditions for suicide.”

The Deacon-Case study helps explain why opioid abuse has grown so dramatically over the past 15 years, and why according to the CDC, the growth has been concentrated among older white Americans. Rather than a rise in irresponsible physician prescriptions, the opioid epidemic seems to have been fueled, in large part, by the same massive economic and social dysfunction driving what Case and Deacon have called “deaths of despair.”

ADDITIONAL ARTICLES

What Physicians Need to Know About Chronic Pain and Opioids

How Physicians Can Better Protect their Patients, the Public and Themselves

Pharmacists Are the Last Line of Defense

View Other Posts

- New Data Suggest Remedial Courses Reduce Recidivism

- Summer School: Reduce Stressors, Avoid Burnout

- Don’t Wait Until it is Too Late: How a Personalized Protection Plan© Decreases Violation Potential

- The What, Why, When, and How of Remedial Educational Interventions

- Revisiting Moral Courage as an Educational Objective