Frequently Asked Questions About Medical Chaperones

Frequently Asked Questions About Medical Chaperones

What is a chaperone?

Some physicians are more likely than others to be familiar with the concept of medical chaperones—those mandated to use them by their boards and those in particular specialties, such as Ob-Gyn and Dermatology. But many physicians have had no exposure to chaperones and still think the term refers to adults keeping an eye on teenagers. Those who look up the term are likely to find a definition like this one: “One who accompanies a physician during physical examination of a patient of the opposite gender (from the physician),” which leads to the next question…

Do I need to use a chaperone if my patient is the same gender as me?

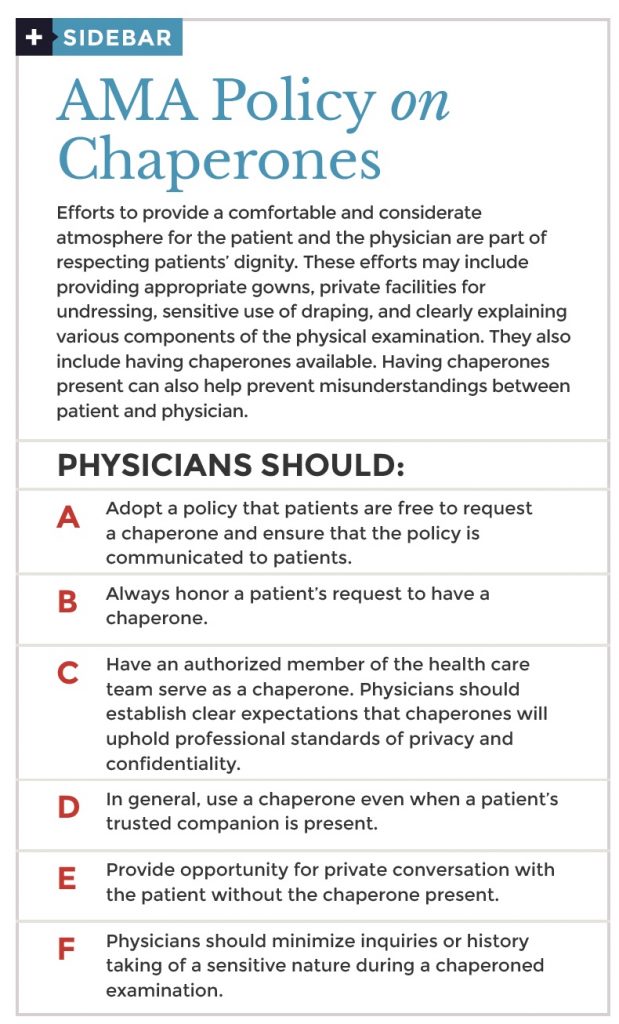

Some experts, including those writing medical dictionaries, still say that chaperones are only needed when your patient is of the opposite gender and undressed. But this view is no longer shared by most in the field. “I know a lot of doctors won’t have a chaperone with a patient of the same sex, but I think that’s simply foolish,” says attorney Jon Porter, “because you don’t know the patient’s sexuality, the patient doesn’t know the provider’s sexuality, and gender doesn’t matter anyway, because anybody can make a complaint against anybody. It’s really a matter of perception.”

The UK’s General Medical Council agrees: “There have been cases where male doctors have been accused by male patients of inappropriate behavior. This suggests a chaperone should be considered irrespective of the doctor’s or the patient’s sex.” The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Ethics is of the same mind: “The request by either a patient or a physician to have a chaperone present during a physical examination should be accommodated regardless of the physician’s sex.”

As Edwin Leap, MD points out in a provocative article, considering the fluidity of gender and sexuality, “Equality means that everyone gets distrusted just as much as everyone else.”

Sex abuse gets a lot of press, but isn’t it really pretty rare? Why worry about such an unlikely problem?

One study estimates that 90% of patients who have suffered sexual violations choose not to report them, which means no one really knows how common or uncommon the problem is. But even assuming it’s rare, as mentioned earlier, chaperones are akin to insurance—protection against rare but potentially catastrophic events.

Are chaperones really effective?

There aren’t any rigorous studies proving that chaperones are effective, but the anecdotal evidence is compelling. “I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of times people with chaperones have been accused of boundary violations,” says Porter. “It can happen still, but it’s very rare.”

What if a patient objects to having a chaperone?

Many patients, both men and women, turn down chaperones when they are offered. (Men are especially resistant, presumably because most chaperones are women). How you should respond depends on your situation. If you are under board orders to have a chaperone, then you must tell the patient that you cannot proceed with the examination. You may offer an alternative—referral to another doctor, for instance—and explain why both the exam and the chaperone are important. But if the patient still refuses a chaperone, you must end the visit.

If you are not legally obligated to use a chaperone, it’s up to you how to proceed. Most professional associations simply suggest that a chaperone be offered and that all requests for a chaperone be honored. Beyond that, you have to weigh the risk and make your own decision.

Some patients always have a family member with them. Can’t they serve as chaperones?

Adult patients with diminished capacity and pediatric patients often have family members with them during exams, as do patients from certain cultures. And many physicians assume that’s enough. But family members are not objective, nor are they concerned with protecting you, the doctor, which is why virtually all experts agree that family members should not be considered chaperones.

I’m concerned some patients won’t tell me things they otherwise would if there’s a chaperone in the room.

Many professional associations recommend offering patients the opportunity to talk with you privately before or after the physical exam. Here’s how the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Ethics puts it: “The presence of a third party in the room may, however, cause some embarrassment to the patient and limit her willingness to talk openly with the physician because of concerns about confidentiality. If a chaperone is present, the physician should provide a separate opportunity for private conversation.”