Treating Family & Friends is a Violation

Treating Family & Friends is a Violation

“But everyone does it.” Why caring for friends and family is almost never a good idea.

It happens every day: someone on staff stops you in the hall and says they have a sinus infection or that their reflux is acting up. They ask you for a prescription or perhaps some samples off the shelf in the office. You may ask a couple of quick questions, but you’re in a hurry, as are they, so you do as they ask and move on—unaware of the risks you’ve taken.

If a regular patient came to you with the same complaint, saying they had sinusitis or reflux, you would take a history, examine them, offer medical advice, answer any questions, address any concerns, arrange for appropriate follow-up and write everything up in their chart. Chances are you did none of these things when you “helped out” your colleague in the hallway. So if anything goes amiss—a bad reaction to the medication, complications from an undiagnosed condition—you are in deep trouble. Depending on the seriousness of the situation, you could face criminal charges, a malpractice suit and/or board discipline up to and including the loss of your license.

From the board’s perspective, the primary problem is not the harm you’ve done to your “patient” or your failure to adhere to what the lawyers call “standard of care;” the board’s fundamental concern is the “dual relationship” you have developed with your colleague/patient.

It’s not uncommon, of course, for physicians and patients to know each other outside the office; in small communities it’s unavoidable. And in most cases, there’s no problem as long as the doctor and patient both understand the differences between their personal and professional relationships and respect the boundaries between the two realms. (Although it’s up to the physician to remain vigilant and refer the patient to another provider if boundary issues emerge.)

The problem arises when the non-medical relationship is serious enough to compromise the doctor-patient relationship. It doesn’t matter if it’s romantic, friendly, familial, social or business-related—nor how confident the physician is that she can remain impartial—every dual relationship jeopardizes the physician’s objectivity and interferes with her ability to focus on the patient’s medical needs, undistracted by any personal concerns. This holds true both at work and at home.

Treating colleagues and friends. The hallway encounter is just one example of the complications that can arise from dual relationships. Consider another workplace scenario. A colleague makes an appointment and comes to see you as a patient. Even assuming you treat him or her as you would any other patient, you are still exposing yourself and your patient to considerable risks.

“When I see a friend or colleague as a patient, I’m both doctor and friend (or colleague), and the dual role may lead me to do too much or too little,” says Mark A. Graber, MD, professor of emergency and family medicine at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

“On the one hand, I may pursue investigations to the nth degree to avoid an error in diagnosis or treatment; I’m too invested in the outcome of this patient. My attitude may cause me to order unnecessary tests, with the patient bearing the attendant risk. For example, I may order a stress test on a low-risk colleague or friend—just to be sure. The result is a false positive, which leads to an invasive cardiac catheterization.

On the other hand, I may have so great an emotional connection with the patient that I do too little. I may avoid potentially painful procedures that I would do if I were guided by more objective clinical judgment. I may perform a lumbar puncture for an “ordinary” patient with a headache and fever without a second thought but may be loath to do one on a friend. Friendship can cloud our judgment.”

Treating family. Rather than bringing a sick spouse or injured child to the family doctor, physicians often provide needed care themselves, especially if the family member is in pain or the doctor’s office is closed for the weekend. Why make someone you love wait for relief when you can instantly provide first-rate compassionate care free of charge?

Although the practice is common, virtually all professional organizations—including the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association (AMA) —warn physicians away from treating family members. The AMA’s Code of Ethics has discouraged the practice since it was first drafted in 1847.

The prohibition is not absolute. According to the AMA’s Code of Medical Ethics (Opinion 8.19), “Physicians should not hesitate to treat themselves or family members until another physician becomes available. In addition, while physicians should not serve as a primary or regular care provider for immediate family members, there are situations in which routine care is acceptable for short-term, minor problems.” When it comes to pain management, however, the AMA cautions physicians not to prescribe controlled substances for family members except in extreme emergencies.

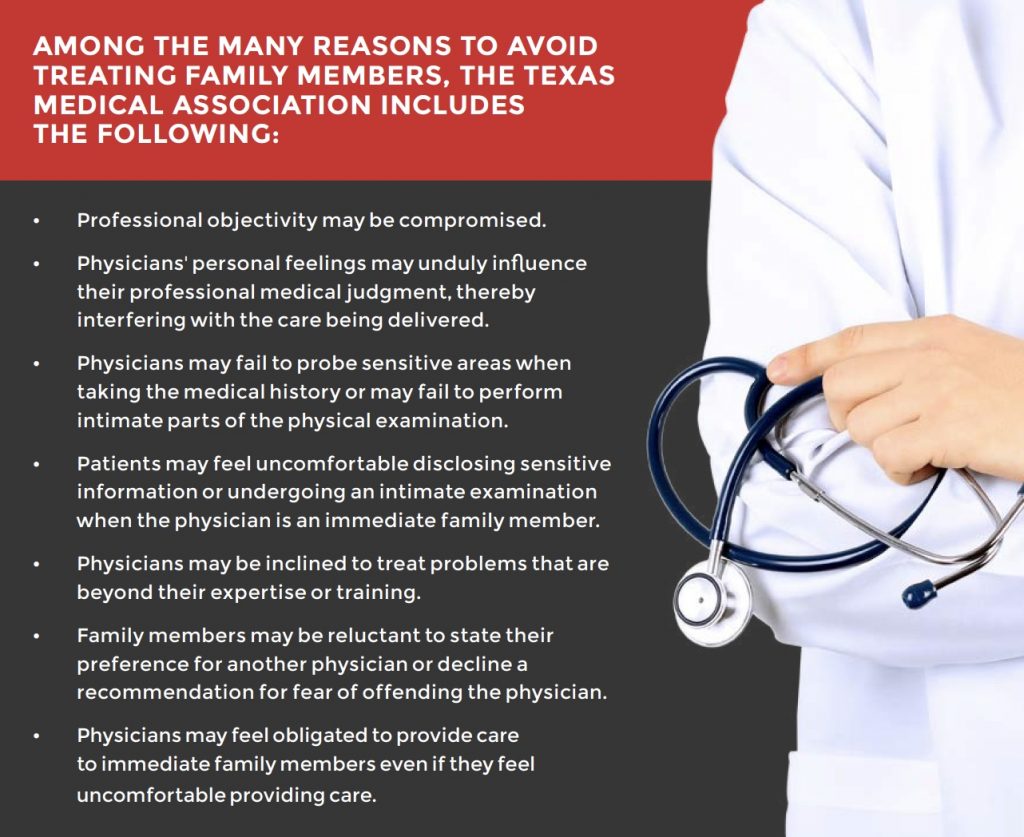

Among the many reasons to avoid treating family members, the Texas Medical Association includes the following:

- Professional objectivity may be compromised.

- Physicians’ personal feelings may unduly influence their professional medical judgment, thereby interfering with the care being delivered.

- Physicians may fail to probe sensitive areas when taking the medical history or may fail to perform intimate parts of the physical examination.

- Patients may feel uncomfortable disclosing sensitive information or undergoing an intimate examination when the physician is an immediate family member.

- Physicians may be inclined to treat problems that are beyond their expertise or training.

- Family members may be reluctant to state their preference for another physician or decline a recommendation for fear of offending the physician.

- Physicians may feel obligated to provide care to immediate family members even if they feel uncomfortable providing care.

Behind each of these reasons stretch numerous cases of personal and professional pain. One ob-gyn treated her own child when he came down with a fever over a weekend. Confident that she knew all she needed to about her son, she didn’t bother to take a full history, as she would have done with a regular patient. Without a proper workup, and unfamiliar with pediatric issues, she misdiagnosed her child and ended up having to rush him to the ER.

In another case, a gastroenterologist provided what he considered “bridge care” for his wife when the couple moved to an area far from the kind of psychiatric care she was accustomed to. When his wife, who suffered from chronic pain, told him she was unable to sleep, he prescribed medication to help ease her discomfort and help her get some rest. Without access to her records, and working outside his area of specialization, he failed to realize that he was over-prescribing and feeding his wife’s growing addiction. When their family doctor examined the wife, she was alarmed by what she found and had her admitted to the hospital. Upon learning that the wife’s husband had been the prescribing doctor, she filed a complaint with the board.