A Broken System's Impact on Physician Burnout

A Broken System’s Impact on Physician Burnout

Empowering clinicians to fix it helps reignite their passion for medicine

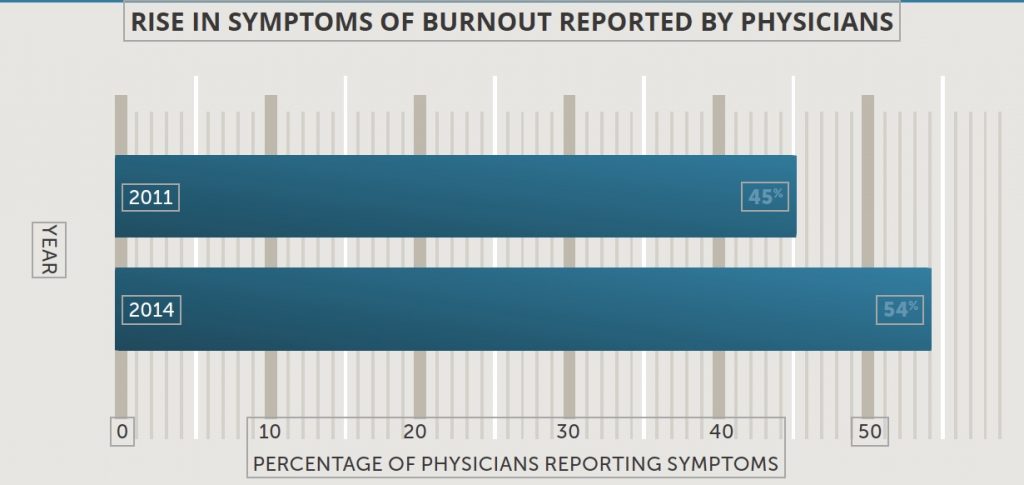

While no one knows exactly what the suicide rate is among physicians (well-meaning colleagues sometimes purposely miscode the cause of death), we do know that burnout is almost always a contributing factor. Physicians in the U.S. are experienceing burn out at an alarming and accelerating rate, according to a recent study. In 2014, 54% reported at least one of the three defining symptoms: physical exhaustion, cynicism, and gnawing doubt that they are making a difference. Three years before, the number was 45%.

Many burnt-out physicians cite lack of control and loss of autonomy as causes of their pain. Rather than allocating their clinical hours as they see fit, based on patients’ needs, they find themselves continually pressured to increase their productivity. Every test and treatment they call for is reviewed, and all too often, denied by insurance companies. Hospital administrators, relying on opinion surveys, criticize their bedside manner instead of appreciating their skill or celebrating their triumphs.

And according to a 2018 report on physician burnout and wellness by the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), “There is worry among some professionals, in medicine and other health care fields, that an expectation for rigid adherence to guidelines will replace what were formerly considered the more elegant, artistic and satisfying aspects of medical practice.”

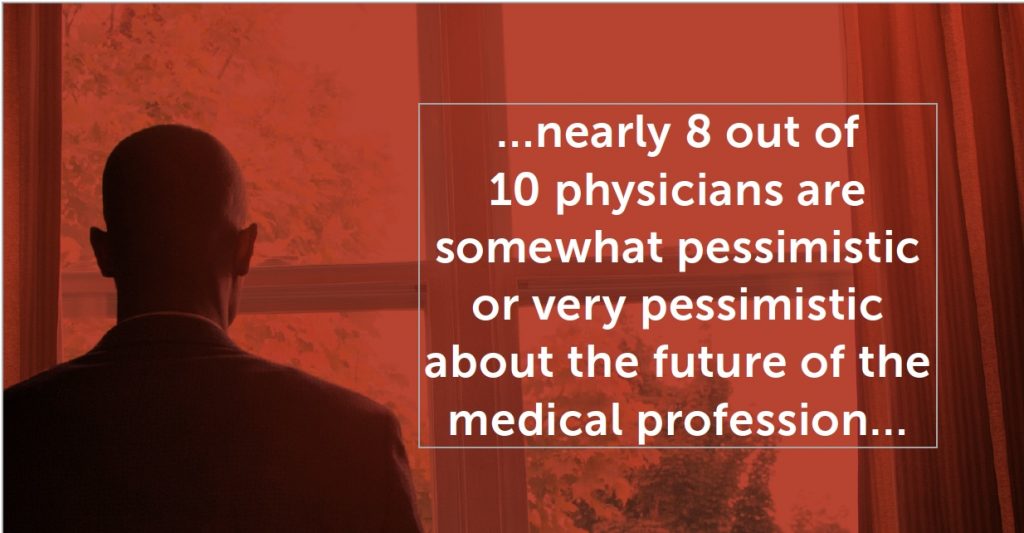

In Doctored: The Disillusionment of an American Physician, cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar says that today’s physicians see themselves not as the “pillars of any community” but as “technicians on an assembly line,” or “pawn[s] in a money-making game for hospital administrators.” No surprise, then, that nearly eight out of 10 physicians are somewhat pessimistic or very pessimistic about the future of the medical profession, according to a 2012 survey.

Frustrations with electronic medical records (EMR) also contribute to burnout. Physicians’ common complaint that they spend more time with computers than with patients was recently borne out by a time and motion study that showed physicians spending 37% of their daily work time on EMRs (not including one to two hours each night), but only 27% interacting directly with patients.

Lack of downtime, including time to sleep, is a major problem among younger physicians. A 2018 study found that interns who worked longer hours than regulations stipulated reported significantly more dissatisfaction with their jobs, morale, personal lives, personal health and, educational experiences. A similar study in 2016 came up with the same results for surgical residents. One physician quoted recently by Wible revealed the desperation behind the statistics.

“I did my internship in internal medicine and residency in neurology before laws existed to regulate resident hours. My first two years were extremely brutal, working 110 to 120 hours/week, and up to 40 hours straight. I got to witness colleagues collapse unconscious in the hallway during rounds, and I recall once falling asleep in the bed of an elderly comatose woman while trying to start an IV on her in the wee hours of the morning.”

MAKING CHANGES, EMPOWERING PHYSICIANS.

While it’s important for physicians to develop coping skills, it’s a mistake to focus exclusively on individual efforts to avoid burnout, says Christina Maslach, a leading authority on burnout and author of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Such efforts tend to blame the victim for the shortcomings of the system. Instead, Maslach emphasizes the need to restructure the workplace.

A Stanford University survey of physicians identified the five work-place improvements respondents valued most highly. In addition to serious real-time help dealing with EMR systems and the use of scribes to relieve some of the EMR drudgery, physicians not only wanted to see improvements in processes and workflow, they wanted to play an active role in making those improvements. Such empowerment is a crucial antidote to the feelings of helplessness that lead to burnout and suicide.

In his book, Physician Suicide: Cases and Commentaries, Peter Yellow-lees, MBBS, MD, describes how one patient came back from the brink of suicide. In reviewing her recovery, Dr. Tina Garland talked about the practical changes she helped promote at the clinic where she practiced. The specifics seemed less important to her than the sense of validation and effectiveness she gained in the process. “I really feel I’m being listened to now,” she said. “And while not all of my ideas get taken up, some certainly do. It’s just so good to know that I and the other doctors and nurses are being listened to. It makes us feel more in control and better respected.”

The Stanford survey provides statistical support for Dr. Garland’s experience. The top-rated improvement strategy was, “Empowering physicians to re-engineer clinical process and flows.” And the Stanford University clinic showing the greatest improvements in professional satisfaction and burnout rate was also the one showing substantial improvement in employee engagement.