Part One: Opioid Crisis-Unraveling the Myths

Part One: Opioid Crisis-Unraveling the Myths

Deaths from opioid overdose have skyrocketed in the past 18 years. While the crisis started with opioid prescriptions, illegal opioids have been fueling the crisis for nearly a decade. The general consensus assigns blame primarily on physicians, with predictable results.

PART 1: Why It Keeps Getting Worse

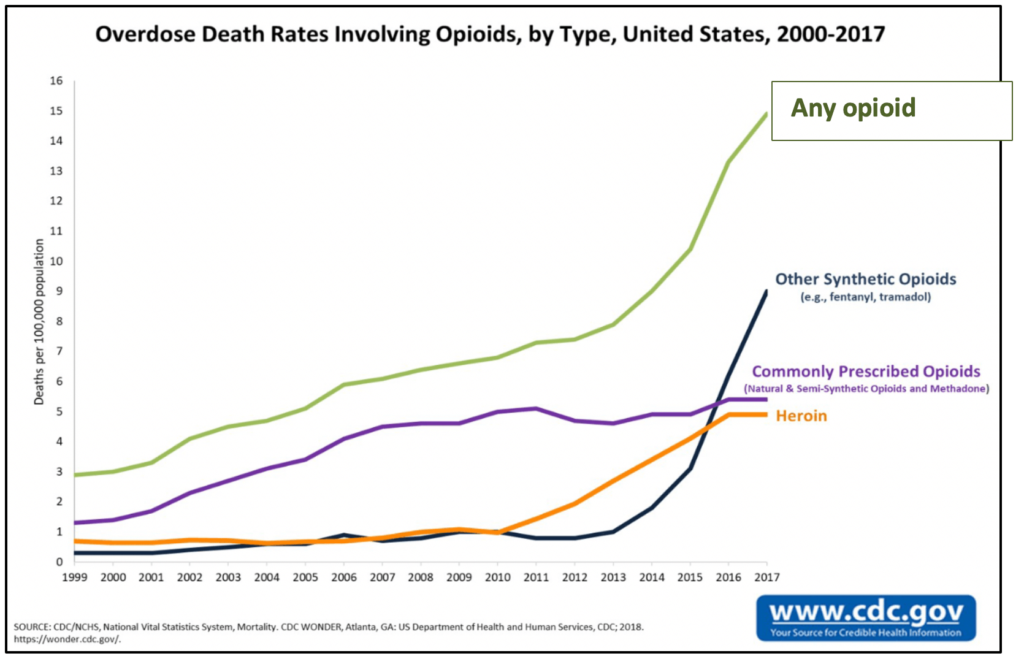

No one disputes that there is an opioid crisis in this country. Nearly 48,000 Americans died after overdosing on opioids in 2017. Even more alarming, the rate at which people are dying from opioid overdose increased five-fold between 1999 and 2017.

What is disputed are the causes of the epidemic and the steps needed to end it. Despite repeated attempts, overdose deaths continue to mount. In fact, it now seems clear that several well-intentioned efforts have actually made things worse.

If you focus solely on the dramatic rise in overdose deaths related to any type of opioid (the green line in the accompanying chart), you might think the opioid crisis was a single unrelenting trend. But take a closer look at how different categories of opioid-related deaths have grown over the past 18 years, and a more complicated picture emerges.

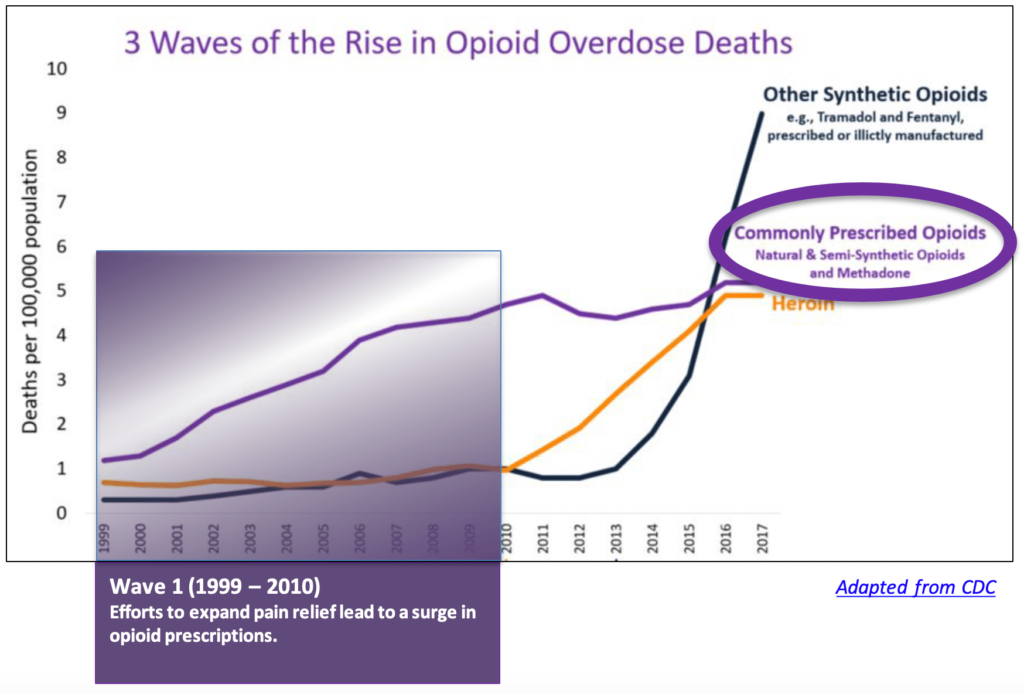

Wave 1: Expanding care for pain patients led to widespread abuse

Until 1986, U.S. physicians largely steered clear of opioids. Mistakenly believing the drugs led inevitably to addiction and death, doctors prescribed them only to terminal cancer patients. That all changed when a 31 year-old cancer specialist named Dr. Russell Portenoy began arguing that millions of non-cancer patients were suffering unnecessarily. In a seminal paper followed by a national campaign, Portnoy claimed that physicians could use opioids to treat non-cancer pain patients safely and effectively.

Many physicians found Portenoy’s arguments persuasive. Many more were convinced by the misleading marketing of companies like Purdue Pharma. When the company launched OxyContin, an extended-release formulation of Oxycodone, in 1996, it invested huge sums in a deceptive marketing effort that downplayed the risks involved. Sales of the drug soared from $48 million when it was introduced to almost $1.1 billion just four years later. Soon, physicians were writing prescriptions by the thousands. According to a recent Vox.com article, “In some counties and states, there were more prescribed bottles of painkillers than there were people.”

As the number of prescriptions climbed, so did the number of overdose deaths (the purple line in the accompanying chart). It was not the patients themselves who were overdosing. What most of the primary doctors prescribing the drugs failed to realize was that many of the pills they prescribed were being stolen or diverted.

On the street, the pills were routinely crushed and then inhaled or injected to produce the high users were looking for. As pain management and addiction specialist Jennifer Schneider, MD, explains, “What produces euphoria is not the concentration of the drug in the brain, but the rate of increase of the drug into the brain.” What made the new delayed-release formulation so appealing was how much more of the active ingredient each pill contained. The immediate-release formulation contains 5 mg to 30 mg of the drug. Each delayed-release pill can have as much as 80 mg. “By crushing an extended-release pill and inhaling or injecting it, you could get a whopping dose of the drug into the brain very quickly,” said Schneider.

The prescriptions came with written warnings about the dangers of crushing the pills. Those who got their drugs on the street corner never saw those warnings.

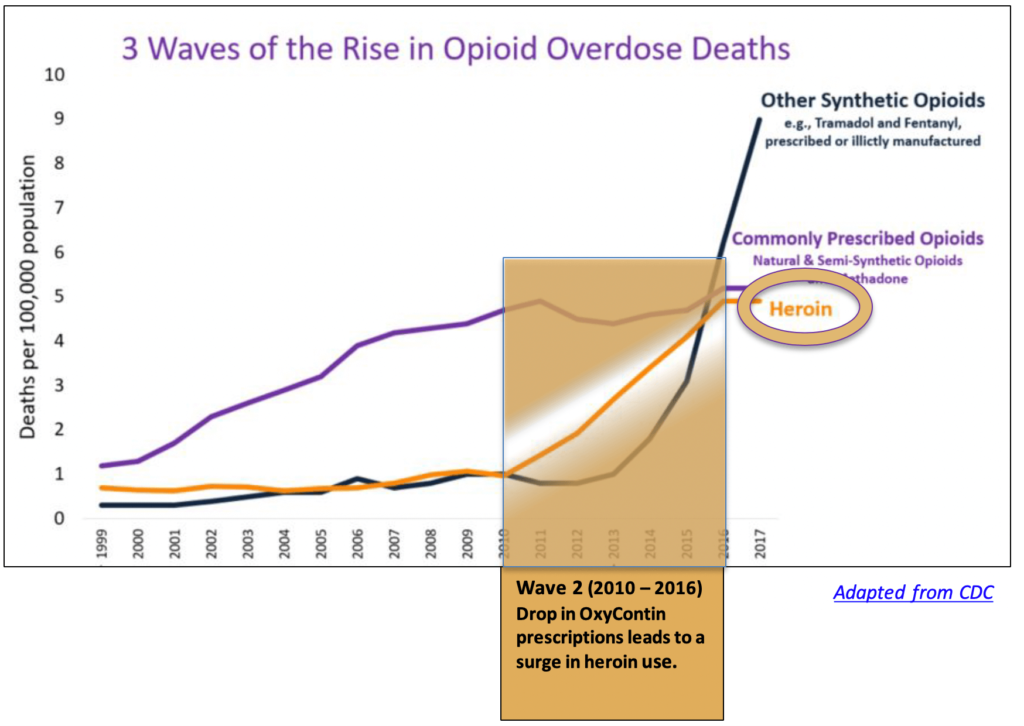

Wave 2: An effort to deter abuse fueled a new phase in the opioid crisis

After 10 years of steady growth, Purdue Pharma pulled Oxycontin from the market in 2010 and replaced it with an abuse-deterrent formulation. The new pills could no longer be crushed to access the Oxycodone they contained. As expected, the street value of the drug plummeted almost immediately, as did the number of overdose deaths from prescribed opioids.

But the new formulation did nothing to slow the overall rise in opioid-related deaths. In fact, the number of such deaths began to surge dramatically following the release of the new abuse-deterrent formulation. A 2019 study in The Review of Economics and Statistics explains why. Now that OxyContin was no longer appealing to opioid abusers, many simply shifted to heroin. The illegal opioid was cheaper and readily available on the street. It was also unregulated, so users never knew how much of the drug they were injecting into their veins, or what it might be laced with. From 2010 until 2016, heroin use and overdose deaths climbed rapidly (the yellow line).

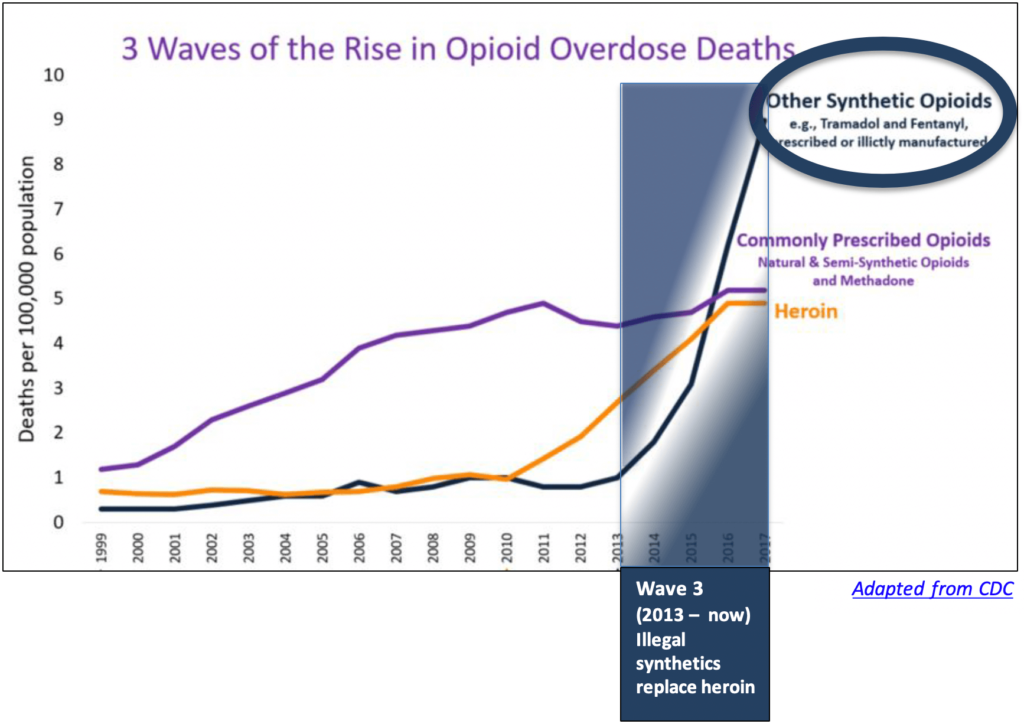

Wave 3: Illegal synthetic opioids are now fueling the crisis — not prescriptions

By 2013, the demand for heroin was outstripping the supply, according to a recent study published in the journal Addiction. To make up the shortfall and keep fueling the illegal market, suppliers turned primarily to fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is cheaper to produce than heroin and 30 to 40 times more powerful. Unlike heroin, fentanyl is produced entirely in the lab, so production can be ramped up whenever suppliers want, regardless of the season and weather conditions. In 2016, fentanyl surpassed heroin as the leading cause of opioid-related overdose deaths (the blue line).

Despite the overwhelming evidence that fentanyl and other illegal synthetic opioids are now driving the crisis, recent efforts to combat overdose deaths have continued to focus on prescriptions. Foremost among these efforts were prescribing guidelines published by the CDC in 2016. The primary recommendations concerned dosage and duration.

- Doctors were told they “should carefully reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks when considering increasing dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/day or carefully justify a decision to titrate dosage to ≥90 MME/day.”

- Physicians were also told they “should prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.”

As numerous experts, including the American Medical Association, have pointed out, these guidelines were widely misinterpreted. “The wording makes it clear that the guidelines apply only to patients who are being started on opioids, not those who have been using them safely under a doctor’s care, often for years,” said Schneider. “But the guidelines are now being used by legislators, pharmacy chains, and insurers to restrict prescriptions for all patients on opioids for any reason.” As a result, “Opioid prescribing has declined substantially across the United States between 2014 and 2017,” according to a recent article in JAMA Network. But since prescribed opioids are no longer driving the opioid crisis — and haven’t been for nearly a decade —this reduction in opioid prescribing has done nothing to slow the rise in overdose deaths. If anything, deaths from fentanyl and other synthetics have increased dramatically since the CDC guidelines were published.

For Schneider and many others, the evidence is clear. “We are absolutely doing the opposite of solving the opioid crisis by continuing to limit prescribing by doctors.” Even worse, the cutback in prescribing is causing pain patients and the physicians who care for them irreparable harm.

View Other Posts

- Summer School: Reduce Stressors, Avoid Burnout

- Don’t Wait Until it is Too Late: How a Personalized Protection Plan© Decreases Violation Potential

- The What, Why, When, and How of Remedial Educational Interventions

- Revisiting Moral Courage as an Educational Objective

- If It Isn’t Documented, It Didn’t Happen