Institutional Vulnerabilities

Institutional Vulnerabilities

More than 20 years of working with clinicians in need of remedial courses has taught PBI Education that all professionals are at risk of committing a boundary violation. Each of us has personal vulnerabilities that can lead to bad decisions in certain situations, especially if we feel no one is watching us. And the more we deny this fact, the more at risk we are.

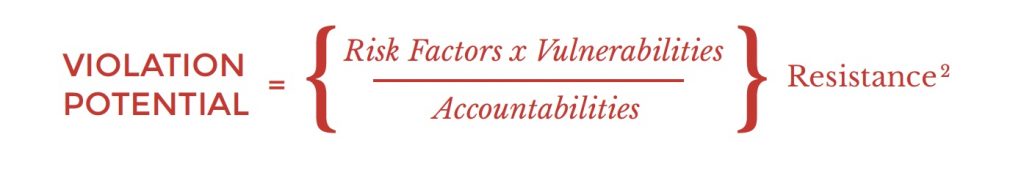

Here’s another way of saying the same thing:

Individuals who understand this formula are far better able to protect themselves and their patients than most practitioners. If a physician understands herself well enough to know her vulnerabilities (the deep, often hidden needs that make her more susceptible to certain temptations), and realizes which situations are most likely to tempt her (risk factors), she can try to avoid potential risks or protect herself from them by ensuring appropriate oversight of one kind of another (accountabilities), such as the use of a chaperone. Most importantly, she can overcome her natural tendency to deny personal weaknesses (resistance) and instead confront them.

What I’ve come to realize as I’ve worked with hospitals and medical groups of all sizes, is that institutions, too, have a violation potential. And it presents real dangers both to the institution and to the physicians, nurses and others it employs.

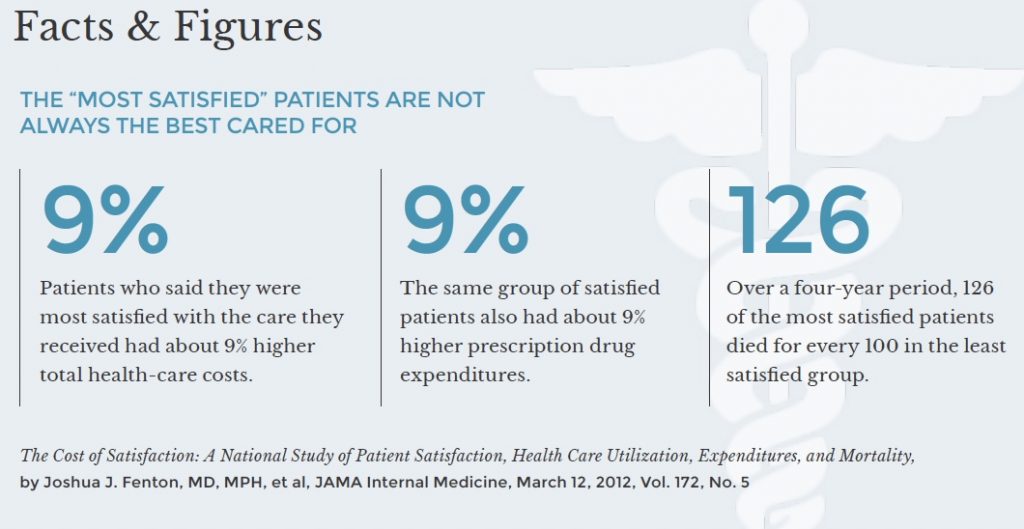

Treating patients as customers — The most common institutional vulnerability I see is hospitals’ tendency to view patients as customers. It’s not surprising that they do, given the federal government’s decision to base 30% of hospitals’ Medicare reimbursement on patient satisfaction survey scores. But as well intentioned as that policy may have been, the results have been horrendous, in terms of both patient health (see below) and professional boundaries.

An article in Hospital and Health Networks makes the change in mindset all too clear. Entitled Treating Patients as Consumers is a Growing Strategy, the article states that, “Patients are likely to start acting more like consumers in the coming years and hospital executives need to be ready.” Providence Health & Services, a large not-for-profit health system, is showcased for hiring “executives from Amazon and other retailers in an effort to shape its consumer-facing strategy.” And the article touts the use of market research “into what consumers want” so that, as one hospital CEO said, the institution can put patients/consumers “at the center of everything that has to be done.”

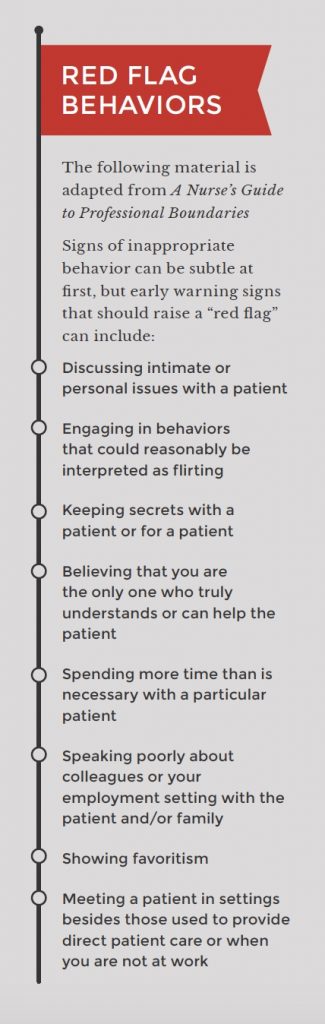

The danger here is that doctors and nurses are being encouraged to do whatever pleases patients, all too often without regard to what is appropriate professional behavior. In fact, financial bonuses frequently depend on how happy patients say they are with the care they receive. Numerous physicians have told me that they were advised to touch patients in ways that would make the patient feel cared for and connected (an arm around the shoulder, a gentle pat on the back). But when you consider that one in four women under the age of 25 has been a victim of sexual trauma, it’s not surprising that such touching can easily be misperceived. And when it comes to boundary violations, perception is everything.

When it’s the patient who acts inappropriately, clinicians are even more hesitant to say anything or tell anyone for fear of offending the “customer.” We had one case where a female patient slapped a doctor on the butt. Later, apparently hurt by his lack of response, she said that he was the one who had slapped her. Since the physician hadn’t said anything to the patient herself, told anyone about the incident at the time or even noted it in the patient’s chart, it was simply his word against hers. And medical boards—created to protect patients, not doctors—almost always take the patient’s word over the doctor’s.

Institutions tend to neglect accountability

One of the primary responsibilities of hospitals and large clinical practices is to provide the oversight needed to protect patients and practitioners. And yet very often institutions fail to ensure the presence of chaperones during physical examinations. Sometimes the reason is financial. Hospitals are under increasing financial pressures, and given the high cost of professional labor, the temptation to do without chaperones is often hard to resist. Other times it’s simply a failure to understand that a chaperone is needed not just to protect the patient but also to protect the physician, and by extension, the hospital.

Assuming that chaperones are needed simply as a reassuring presence for the patient, too often hospitals require them only in intimate exams, when, in fact, the majority of cases that end up in our courts involve non-intimate, un-chaperoned exams. Hospital policy often leaves the decision about whether or not to have a chaperone up to the patient. The problem, then, is that if the patient declines, that doctor has just eliminated a key protection of his license, and the hospital has just opened itself up to a lawsuit.

A male physician once told me that during an office visit he innocently asked a female patient if she’d like to buy a ticket to a charitable dinner-dance. The patient thought he was inviting her to go out with him. With no chaperone to clarify what really happened, a simple misunderstanding quickly escalated, and the physician was soon facing a three-year probation and the loss of his job.

Several of our clients have also told us that they have been cautioned by supervisors not to put anything controversial in a patient’s chart. The lawyers who teach at PBI say just the opposite. Like a chaperone, documentation is a vital protection for the clinician (and a warning to future practitioners). If the doctor who was slapped on the butt had noted the incident in the patient’s chart, he would have at least had some defense against the charge leveled against him.

Institutional resistance has reached epidemic proportions

At the individual level, it’s often senior practitioners who most resist facing up to problems. Reasoning that they have seen it all, they feel immune. They aren’t. Senior people show up in our classes all the time, generally in a state of shock, saying that they can’t believe what’s happening to them.

The same kind of complacency afflicts institutions. Even when there have been a series of boundary violations, a hospital with a long and distinguished history is likely to deny any problem or feel that it is perfectly capable of handling matters on its own. Like the individual, the hospital feels that it’s weathered so much over so long a time that there’s nothing it can’t handle.

Unfortunately, it is all too true that institutions often can avoid their own culpability simply by firing a doctor or nurse who has gotten in trouble. If there are a string of incidents, the temptation is to “clean house” and declare the problem solved, rather than take a hard look at how the institution might be contributing to the problem. By treating the symptom (clinicians who are violating boundaries), instead of the disease (policies or a culture that encourages such violations), these hospitals all but guarantee that the problem will persist.

Fear of alienating potential customers also plays a role here. Hospitals would rather ignore possible problems than risk making them public. But ignoring symptoms is even worse than just treating them. When hospitals fail to acknowledge incidents, they make it all too clear to clinicians that they will not be held accountable.

That was the problem at South Coast Health in Georgia, a multi-specialty practice with about 80 physicians. If someone crossed a boundary, everyone else tended to look the other way. The culture, still young at the time, was completely laissez-faire.

But when the local medical board got involved in a couple of cases, the group’s board of directors decided it was time to make a change. They sent a few people to our boundaries class and then invited me down to give a two-hour presentation. My goal was to make it clear to everyone in the practice that boundary violations are all too common, that they were all vulnerable and that the consequences could be catastrophic.

That talk served as a kind of orientation that helped jump-start a concerted and sustained effort by the group to change the way it dealt with boundary crossings and violations. Two years later, I am happy to report that the number of students we see from South Coast Health has declined dramatically. And when someone does show up, it is generally a proactive intervention to help individuals avoid, rather than overcome a serious problem.

View Other Posts

- Summer School: Reduce Stressors, Avoid Burnout

- Don’t Wait Until it is Too Late: How a Personalized Protection Plan© Decreases Violation Potential

- The What, Why, When, and How of Remedial Educational Interventions

- Revisiting Moral Courage as an Educational Objective

- If It Isn’t Documented, It Didn’t Happen